Archaeology, “External Evidence,” and Groundhog Day in the Comment Section

Welcome back to Taste of Truth Tuesdays, where we stay curious, stay skeptical, and keep a healthy distance from any dogma, whether it’s wrapped in a Bible verse or a political ideology.

This is Part Two of my Jesus Myth series, and I’m going to be straight with you:

This one is a doozy.

Buckle up, buttercup. Feel free to pause and come back.

Originally, the plan was to bring David Fitzgerald back for another conversation. If you listened to Part One, you know he’s done a ton to popularize the idea that Jesus never existed and to dismantle Christian dogma. I still agree with the core mythicist claim: I don’t think the Jesus of the Gospels was a real historical person. If you missed it, here is the link.

But agreeing with someone’s conclusion doesn’t mean I hand them a free pass on how they argue.

After our first interview, I went deeper into Fitzgerald’s work and into critiques of it (especially Tim O’Neill’s long atheist review that absolutely shreds his method.) While his critique of Fitzgerald’s arguments is genuinely useful; his habit of branding people with political labels (“Trump supporter,” “denier”) to discredit them is… very regressive.

It’s the same purity-testing impulse you see in progressive (should be regressive) spaces, just performed in a different costume.

And that’s what finally pushed me over the edge:

The more I watch the atheist/deconstruction world online, the more it reminded me of the exact rigid, dogmatic cultures people say they escaped.

Not all atheists, obviously. But a very loud chunk of that ecosystem runs on:

- dunking, dog-piling, and humiliation

- tribal loyalty, not actual inquiry

- “You’re dead to me” energy toward anyone who may lean conservative or shows nuance

It’s purity culture in different branding.

Then I read how Fitzgerald responded to critics in those archived blog exchanges (not with clear counterarguments) but with emotional name-calling and an almost devotional defense of his “hero and mentor,” Richard Carrier. For me, that was a hard stop.

Add to that: his public Facebook feed is full of contempt for moderates, conservatives, “anti-vaxxers,” and basically anyone outside progressive orthodoxy. My audience includes exactly those people. This space is built for nuance for people who’ve already escaped one rigid belief system and are not shopping for a new one.

He’s free to have his politics.

I’m free not to platform that energy.

So instead of Part Two with a guest, you’re getting something I honestly think is better:

- me (😜)

- a stack of sources

- a comment section that turned into a live demo of modern apologetics

- and a segment at the end where I turn the same critical lens on the mythicist side — including Fitzgerald himself

Yes, we’re going there. Just not yet.

Previously on Taste of Truth…

In Part One, I unpacked why “Jesus might never have existed” is treated like a taboo thought — even though the historical evidence is thin and the standards used to “prove” Jesus would never pass in any other field of ancient history.

Then, in a Taste Test Thursday episode, I zoomed out and asked:

Why do apologists argue like this at all?

We walked through:

- early church power moves

- modern thought-stopping tricks

- and Neil Van Leeuwen’s idea of religious “credences,” which don’t function like normal factual beliefs at all

That episode was about the machinery.

Today is about the evidence. Especially the apologetic tropes that showed up in my comments like a glitching NPC on repeat.

⭐ MYTHS #6 & #7 — “History and Archaeology Confirm the Gospels”

Apologists treat it like a smoking gun.

It contains… one complete word: ‘the.’

These two myths always show up together in the comments, and honestly, they feed off each other. People claim, “history confirms the Gospels,” and when that collapses, they jump to “archaeology proves Jesus existed.” So, I’m combining them here, because the evidence (and the problems) overlap more than apologists want to admit.

In short:

Archaeology confirms the setting. History confirms the existence of Christians.

Neither confirms the Jesus of the Gospels.

And once you actually look at the evidence, the apologetic scaffolding falls apart fast.

1. What Archaeology Really Shows (and What It Doesn’t)

If Jesus were a public figure performing miracles, drawing crowds, causing disturbances, and being executed by Rome, archaeology should show something tied to him or to his original movement.

Here’s what archaeology does show:

- Nazareth existed.

- Capernaum existed.

- The general layout of Judea under Rome.

- Ritual baths, synagogues, pottery, coins.

- A real Pilate (from a fragmentary inscription).

That’s the setting.

Here’s what archaeology has never produced:

- no house of Jesus

- no workshop or tools

- no tomb we can authenticate

- no inscription naming him

- no artifacts linked to the Twelve

- no evidence of a public ministry

- no trace of Gospel-level notoriety

Not even a rumor in archaeology that points to a miracle-working rabbi.

Ancient Troy existing doesn’t prove Achilles existed.

Nazareth existing doesn’t prove Jesus existed.

Apologists push the setting as if it confirms the character. It doesn’t.

2. Geography Problems, Anachronisms & Literary Tells

If the Gospels were eyewitness-based biographies, their geography would line up with first-century Palestine.

Instead, we get:

• Towns that don’t match reality

The Gerasene/Gadarene/Gergesa demon-pig fiasco moves between three different locations because the original story (Mark) puts Jesus 30 miles inland… nowhere near a lake or cliffs.

• Galilee described like a later era

Archaeology shows Galilee in the 20s CE was:

- taxed to the bone

- rebellious

- dotted with large Romanized cities like Sepphoris and Tiberias

But the Gospels portray quaint fishing villages, peaceful Pharisees, and quiet countryside. This reflects post-70 CE Galilee: the era when the Gospels were actually written.

• Homeric storms on a tiny lake

Mark treats the Sea of Galilee like the Aegean (raging storms, near capsizings, disciples fearing death) even though ancient critics mocked this because the “sea” is a small lake.

Dennis MacDonald shows Mark lifting whole scenes from Homer, which explains the mismatch: his geography serves his literary needs, not the historical landscape.

• Joseph of “Arimathea” (a town no one can find)

Carrier and others point out the name works more like a literary pun (“best disciple town”) than a real toponym.

• Emmaus placed at different distances

Luke places it seven miles away. Other manuscripts vary. There was no fixed memory.

These aren’t the mistakes of people writing about their homeland.

They’re the mistakes of later authors constructing a symbolic landscape.

3. The Gospel Trial Scenes: Legally Impossible

This is the part Christians never touch.

One of the most respected legal scholars of ancient Jewish law did a line-by-line analysis of the Gospel trial scenes. He wasn’t writing from a religious angle, he approached it strictly as a historian of legal procedure.

His conclusion?

The trial described in the Gospels violates almost every rule of how Jewish courts actually worked.

According to his research:

- capital trials were never held at night

- they were not allowed during festivals like Passover

- capital verdicts required multiple days, not hours

- the High Priest did not interrogate defendants

- witness testimony had to match

- beating a prisoner during questioning was illegal

- and Jewish courts didn’t simply hand people over to Rome

When you stack these facts together, it becomes clear:

The Gospel trial scenes aren’t legal history…. they’re theological storytelling.

That’s before we even get to Pilate.

Pilate was not a timid bureaucrat.

He was violent, ruthless, removed from office for brutality.

4. Acts Doesn’t Remember Any Gospel Miracles

If Jesus actually:

- drew crowds,

- fed thousands,

- raised the dead,

- blacked out the sun,

- split the Temple curtain,

- and resurrected publicly…

Acts (written after the Gospels) should remember all of this.

Instead:

- No one in Acts has heard of Jesus.

- No one mentions an empty tomb.

- No one cites miracles as recent events.

- Roman officials are clueless.

- Paul knows Jesus only through visions and the scriptures.

Acts behaves exactly like a community whose “history” was not yet written.

5. Manuscripts: Many Copies, No Control

Apologists love saying:

“We have 24,000 manuscripts!”

Quantity isn’t quality.

- almost all are medieval

- the earliest are tiny scraps

- none are originals

- no first-century copies

- scribes altered texts freely

- entire passages were added or deleted

- six of Paul’s letters are pseudonymous

- many early Christian writings were forged

Even Origen admitted that scribes “add and remove what they please” (privately, of course.)

The manuscript tradition looks nothing like reliable preservation.

6. The Church Fathers Don’t Help (and They Were Tampered With Too)

This is where Fitzgerald’s chapter hits hardest.

Before 150 CE, we have:

- no Church Father quoting any Gospel

- no awareness of four distinct Gospels

- no clear references to Gospel events

Justin Martyr (writing in the 150s) is the first to quote anything Gospel-like, and:

- he never names Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John

- many of his quotes don’t match our Gospels

- he calls them simply “the memoirs”

Even worse:

The writings of Ignatius, Polycarp, Dionysius of Corinth, and many others were tampered with.

Some were forged entirely.

So the apologetic claim “The Fathers confirm the Gospels” collapses:

They don’t quote them.

They don’t know them.

And their own texts are unstable.

Metzger claimed we could reconstruct the New Testament from the Fathers’ quotations but his own scholarship shows the Fathers don’t quote anything reliably until after the Gospels were circulating.

7. External Pagan Sources: Late, Thin, and Dependent on Christian Claims

This is the other half of the myth… that “history” outside the Bible confirms Jesus.

Let’s look quickly:

• Tacitus (116 CE)

Reports what Christians of his day believed.

He cites no source, no archive, no investigation.

• Pliny (c. 111 CE)

Says Christians worship Christ “as a god.”

Confirms Christians existed — not that Jesus did.

• Josephus (93 CE)

The Testimonium is tampered with.

Even conservative scholars admit Christian hands were all over it.

The “James, brother of Jesus” line is ambiguous at best.

These are not independent confirmations.

They’re late echoes of Christian claims.

In closing:

You can confirm:

- towns

- coins

- synagogues

- political offices

- geography

But that only shows the world existed, not the characters.

The Gospels are theological narratives composed decades later, stitched out of scripture, symbolism, literary models, and the needs of competing communities.

Archaeology confirms the backdrop.

History confirms the movement.

Neither confirms the biography.

Once you strip away apologetic spin, the evidence points to late, literary, constructed narratives, not eyewitness records of a historical man.

Myth #8: “Paul and the Epistles Confirm the Gospels”

Albert Schweitzer pointed out that if we only had Paul’s letters, we would never know that:

- Jesus taught in parables

- gave the Sermon on the Mount

- told the “Our Father” prayer

- healed people in Galilee

- debated Pharisees

From Paul and the other epistles, you wouldn’t even know Jesus was from Nazareth or born in Bethlehem.

That alone should make us pause before saying, “Paul confirms the Gospels.”

Paul’s “Gospel” Is Not a Life Story

When Paul says “my gospel,” he doesn’t mean a narrative like Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John. His gospel is:

- Christ died for our sins

- was buried

- was raised

- now offers salvation to those who trust him

No:

- Bethlehem, Nazareth, Mary, Joseph

- John the Baptist

- miracles, exorcisms, parables

- empty tomb story with women at dawn

And this isn’t because Paul is forgetful. His letters are full of perfect moments to say, “As Jesus taught us…” or “As we all know from our Lord’s ministry…”

He never does.

Instead, he appeals to:

- his own visions

- the Hebrew scriptures (in Greek translation, the Septuagint)

- what “the Lord” reveals directly to him

For Paul, Christ is:

- “the image of the invisible God”

- “firstborn of all creation”

- the cosmic figure through whom all things were made

- the one who descends to the lower realms, defeats spiritual powers, and ascends again

That is cosmic myth language… not “my friend’s rabbi who did a lot of teaching in Galilee a few decades ago.”

The “Lord’s Supper,” Not a Last Supper

The one place people think Paul lines up with the Gospels is 1 Corinthians 11, where he describes “the Lord’s Supper.”

Look closely:

- He never calls it “the Last Supper.”

- He never says it was a Passover meal.

- He never places it in Jerusalem.

- He says he received this ritual from the Lord, not from human eyewitnesses.

The phrase he uses, kuriakon deipnon (“Lord’s dinner”), is the same kind of language used for sacred meals in pagan mystery cults.

The verb he uses for “handed over” is used elsewhere of God handing Christ over, or Christ handing himself over not of a buddy’s betrayal. The specific “Judas betrayed him at dinner” motif shows up later, in the Gospels.

Then, when later authors retell the scene, they can’t even agree on the script. We get:

- Paul’s version

- Mark’s version

- Matthew’s tweak on Mark

- Luke’s two different textual forms

- and John, who skips a Last Supper entirely and relocates the “eat my flesh, drink my blood” thing to a synagogue sermon in Capernaum

That looks less like multiple eyewitness reports and more like a liturgical formula evolving as it gets theologized.

Hebrews and the Missing Connection

The author of Hebrews:

- goes deep on covenant and sacrificial blood

- quotes Moses: “This is the blood of the covenant…”

- spends time on Melchizedek, who brings bread and wine and blesses Abraham

In other words:

The author sets up what would be a perfect sermon illustration for the Last Supper… but he never takes it. No “as our Lord did on the night he was betrayed.” No Eucharist scene. No Passover meal.

The simplest explanation:

He doesn’t know that story. He knows the ritual meaning; the later narrative scene in Jerusalem hasn’t been invented yet in his circle.

How Paul Says He Knows Christ

Paul is very clear about his source:

- He did not receive his gospel from any human (Galatians 1).

- He barely met the Jerusalem “pillars,” waited years to even visit them, and insists they added nothing to his message.

- He says God “revealed his Son in me.”

- His scriptures are the Septuagint, which he reads as a giant coded story about Christ.

In other words, for Paul:

- Christ is a hidden heavenly figure revealed in scripture and visions.

- The “mystery” has just now been unveiled.

That only makes sense if there wasn’t already a widely known human teacher whose sayings and deeds were circulating everywhere.

The Silence of the Other Epistles

If it were just Paul, we could say, “That’s just Paul being weird.”

But the pattern runs across the other epistles:

From the New Testament letters outside the Gospels and Acts, you would never know:

- Jesus was from Nazareth or born in Bethlehem

- he grew up in Galilee

- he taught crowds, told parables, healed people, or exorcised demons

- he had twelve disciples, one of whom betrayed him

- there were sacred sites tied to his life in Jerusalem

“Bethlehem,” “Nazareth,” “Galilee” do not appear in those letters with reference to Jesus. Jerusalem is never presented as, “You know, the place where all this just happened.”

The supposed “brothers of the Lord” never act like family with stories to tell. The letters attributed to James and Jude don’t even mention they’re related to Jesus.

When these early authors argue about circumcision, food laws, purity, and ethics, they consistently go back to the Old Testament…not to anything like a Sermon on the Mount.

That is very hard to reconcile with a memory of a recent, popular Galilean preacher inspiring the entire movement.

Myth #9: “Christianity Began With Jesus and His Twelve Besties”

If you grew up on Acts, you probably have this movie in your head:

- Tiny, persecuted but unified Jesus movement

- Centered in Jerusalem

- Led by Jesus’ family and the Twelve

- Paul shows up later in season two as the complex antihero

That’s the canonical story.

When you step back and read our earliest sources on their own terms, that picture melts.

Fragmented from the Start

In 1 Corinthians, Paul complains:

“Each of you says, ‘I belong to Paul,’ or ‘I belong to Apollos,’ or ‘I belong to Cephas,’ or ‘I belong to Christ.’ Is Christ divided?” (1 Cor. 1:12–13)

That’s not “one unified church.”

He also:

- rants about people “preaching another Jesus”

- calls rival apostles “deceitful workers,” “false brothers,” “servants of Satan”

- invokes curses on those preaching a different gospel (Gal. 1:6–9; 2 Cor. 11)

Meanwhile, the early Christian manual Didakhē warns communities about wandering preachers who are just “traffickers in Christs” (what Bart Ehrman nicknames “Christ-mongers.”)

Right away, we see:

- multiple groups using the Christ label

- competing versions of what “the gospel” even is

- no sign of one tight central group everyone agrees on

Different Jesuses for Different Communities

By the time the Gospels and later texts are in circulation, we can already see:

- Paul’s Christ: a cosmic, heavenly savior, revealed in scripture and visions, ruling spiritual realms

- Thomasine Christ: in the Gospel of Thomas, salvation comes through hidden wisdom; there’s no crucifixion or resurrection narrative

- Mark’s Jesus: a suffering, misunderstood Son of God who’s “adopted” at baptism and abandoned at the cross

- John’s Jesus: the eternal Logos, present at creation, walking around announcing his unity with the Father

- Hebrews’ Christ: the heavenly High Priest performing a sacrifice in a heavenly sanctuary

These are not just “different camera angles on the same historical guy.” They reflect:

- different liturgies

- different cosmologies

- different starting assumptions about who or what Christ even is

And notice: there is no clean pipeline from “this man’s twelve students carefully preserved his teachings” into this wild diversity.

Paul vs. Peter: Not a Cute Disagreement

Acts spins the Jerusalem meeting as:

- everyone sits down

- hashes things out

- walks away in perfect unity

Paul’s own account (Galatians 2) is… not that:

- he calls some of the Jerusalem people “false brothers”

- he says they were trying to enslave believers

- he says he “did not yield to them for a moment”

- he treats the supposed “pillars” (Peter, James, John) as nobodies who “added nothing” to his gospel

That’s not a friendly staff meeting. That’s two rival Christianities:

- a more Torah-observant, Jerusalem-centered Jesus-sect

- Paul’s law-free, Gentile-mystic Christ-sect

Acts, written later, airbrushes this into harmony. The letters show how close the whole thing came to a full split.

Where Are the Twelve?

If Jesus’ twelve disciples were:

- real,

- the main founders of Christianity,

- traveling around planting churches,

we’d expect:

- lots of references to them

- preserved teachings and letters

- at least some reliable biographical detail

Instead:

- the lists of the Twelve don’t agree between Gospels

- some manuscripts can’t even settle on their names

- outside the Gospels and Acts, the Twelve basically vanish from the first-century record

Paul:

- never quotes “the Twelve”

- never appeals to them as the final authority

- treats Peter, James, John simply as rival apostles, not as Jesus’ old friends

We have no authentic writings from any of the Twelve. The later “Acts of Peter,” “Acts of Andrew,” “Acts of Thomas,” etc., are generally acknowledged to be later inventions.

The simplest explanation is not that the Twelve were historically massive and weirdly left no trace. It’s that:

- “The Twelve” are symbolic: twelve tribes, twelve cosmic seats, twelve zodiac signs, take your pick.

- Their names and “biographies” were built after the theology, not before.

The Kenosis Hymn: Jesus as a Title, Not a Birth Name

In Philippians 2, Paul quotes an early hymn:

“Being found in human form, he humbled himself

and became obedient to the point of death — death on a cross.

Therefore God highly exalted him

and gave him the name that is above every name,

so that at the name of Jesus every knee should bow…”

Notice:

- The hymn does not say God gave him the title “Lord.”

- It says God gave him the name Jesus after the exaltation.

That is not what you expect if “Jesus” was already the known name of a village carpenter from Nazareth. It makes a lot more sense if:

- “Jesus” functions originally as a divine name for a savior figure (“Yahweh saves”),

- assigned in the mythic story after his cosmic act,

- and only later gets retrofitted as the everyday name of a human hero.

Mark: From Mystery Faith to “Biography”

All of this funnels into the earliest Gospel: Mark.

Mark announces up front that he’s writing a gospel, not a biography. Modern scholars have shown that Mark:

- builds scenes out of Old Testament passages

- mirrors patterns from Greek epics

- structures the story like a giant parable, where insiders are given “the mystery of the kingdom,” and outsiders only get stories

In Mark’s own framework, Jesus speaks in parables so that many will see but not understand. The whole Gospel plays that way: symbolic narrative first, later read as straight history once the church gains power.

So did Christianity “begin with Jesus and his apostles”?

If by that you mean:

One coherent movement, founded by a famous rabbi with twelve close disciples, faithfully transmitted from Jerusalem outward…

Then no. That’s the myth.

What we actually see is:

- multiple competing Jesuses

- rival gospels and factions

- no clear paper trail from “Jesus’ inner circle”

- later authors stitching together a cleaned-up origin story and branding rivals as “heresy”

Biographies came after belief, not before.

Myth #10: “Christianity Was a Miraculous Overnight Success That Changed the World”

The standard Christian flex goes like this:

“No mere myth could have spread so fast and changed the world so profoundly. That proves Jesus was real.”

Let’s slow that down.

But before we even touch the growth rates, we need to name something obvious that apologists conveniently forget:

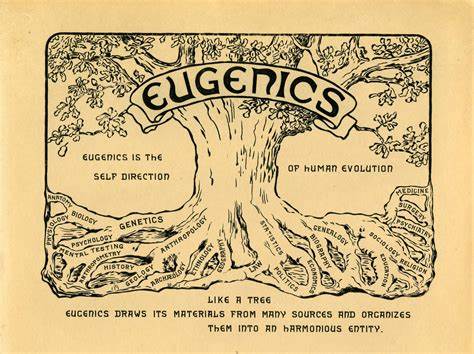

Christianity wasn’t the first tradition built around a dying-and-rising savior. Not even close.

Long before the Gospels were written, the ancient Near East had already produced fully developed resurrection myths. One of the oldest (and one of the most important) belonged to Inanna, the Sumerian Queen of Heaven.

Inanna’s Descent (c. 2000–3000 BCE) is the earliest recorded resurrection narrative in human history.

She descends into the Underworld, is stripped, judged, executed, hung on a hook, and then through divine intervention, is brought back to life and restored to her throne.

Learn more about the story of Inanna here.

This story predates Christianity by two thousand years and was well known across Mesopotamia.

In other words:

✨ The idea that a divine figure dies, descends into darkness, and returns transformed was already ancient before Christianity was even born.

So, the claim that “no myth could spread unless it were historically real” falls apart immediately. Myths did spread. Myths do spread. Myths shaped entire civilizations long before Jesus entered the story.

Now (with that context in place) let’s actually talk about Christianity’s growth..

Christianities Stayed Small…. Until Politics Changed

Carrier’s modeling makes it clear:

- even if you start with generous numbers (say 5,000 believers in 40 CE),

- you still don’t get anywhere near a significant percentage of the Empire until well into the third century

And that includes all groups who believed in some form of Christ — including the later-branded “heretics.”

So, for the first ~250 years, Christianity:

- is tiny

- is fragmented

- is one cult among many in a very crowded religious landscape

The “miracle” is not early explosive growth. It’s what happens when their tiny, disciplined network suddenly gets access to empire-level power.

Rome Falls; Christianity Rises

Fitzgerald is right that Christianity benefitted from Rome’s third-century crisis:

- chronic civil wars

- inflation and currency debasement

- border instability and barbarian incursions

- trade networks breaking down

- urban life contracting

As conditions worsened:

- Christianity’s disdain for “worldly” culture

- its emphasis on endurance, suffering, and heavenly reward

- its growing bishop-led structure and charity networks

…all became more attractive to the poor and dispossessed.

“It was a mark of Constantine’s political genius … that he realized it was better to utilize a religion … that already had a well‑established structure of authority … rather than exclude it as a hindrance.” Charles Freeman, The Closing of the Western Mind: The Rise of Faith & the Fall of Reason

But there’s a step many historians including Fitzgerald often underplay:

How Christianity destroyed the classical world.

From Tolerated to Favored to Tyrannical

A quick timeline:

- 313-Constantine legalizes Christianity (Edict of Milan). Christianity is now allowed, not official. Constantine still honors Sol Invictus and dies as a pagan emperor who also patronized bishops.

- 4th century– Christian bishops gain wealth and political leverage. Imperial funds start flowing to churches. Pagan temples begin to be looted or repurposed.

- 380– Emperor Theodosius I issues the Edict of Thessalonica: Nicene Christianity becomes the official state religion.

- 395 and after– Laws begin banning pagan sacrifices and temple worship. Pagan rites become crimes.

Catherine Nixey’s The Darkening Age and Charles Freeman’s The Closing of the Western Mind document how this looked on the ground:

- temples closed, looted, or destroyed

- statues smashed

- libraries and shrines burned

- philosophers harassed, exiled, or killed

- non-Christian rites criminalized

Christianity didn’t “persuade” its way to exclusive dominance. It:

- received funding and legal favor

- then helped outlaw and dismantle its competition

That is not a moral judgment; it’s just how imperial religions behave.

The “Overnight Success” That Took Centuries and a State

So was Christianity a new, radically different, overnight success?

- Not new: it recycled the son-of-god savior pattern, sacred meals, initiation, and rebirth themes common in the religious world around it. Even early church fathers admitted the similarities and blamed them on Satan “counterfeiting” Christianity in advance.

- Not overnight: it stayed statistically tiny for generations.

- Not purely spiritual success: it became powerful when emperors needed an obedient, centralized religious hierarchy to stabilize a collapsing state.

Christianity didn’t “win” because its evidence was overwhelming.

It won because:

- it fit the needs of late-imperial politics

- it built a strong internal hierarchy

- it could supply social services

- its leaders were willing to suppress, outlaw, and overwrite rival traditions

This is not unique. It’s a textbook case of how state-backed religions spread.

Why the Pushback Always Sounds the Same

After Part One, my comment sections turned into Groundhog Day:

- “You’re ignoring Tacitus and Josephus!”

- “Every serious scholar agrees Jesus existed.”

- “Archaeology proves the Bible.”

- “There are 25,000 manuscripts.”

- “Paul met Jesus’ brother!”

- “If Jesus wasn’t real, who started Christianity?”

- “Ancient critics never denied his existence — checkmate.”

- “You just hate religion.”

- “This is misinformation.”

Different usernames. Same script.

This is where Neil Van Leeuwen’s work on religious credences helps:

- Factual beliefs are supposed to track evidence. If you show me credible new data, I update.

- Religious credences function differently: they’re tied to identity, community, and morality. Their job isn’t to track facts; it’s to hold the group together.

So when you challenge Jesus’ historicity, you’re not just questioning an ancient figure. You’re touching:

- “Who am I?”

- “Who are my people?”

- “What makes my life meaningful?”

No wonder people come in hot.

That doesn’t make them stupid or evil. It just means the conversation isn’t really about Tacitus. It’s about identity maintenance.

Now Let’s Turn the Lens on Mythicism (Yes, Including Fitzgerald)

Here’s where I want to be very clear:

- I am a mythicist.

- I do not think the Jesus of the Gospels ever existed as a historical person.

But mythicism itself doesn’t get a free pass.

Carrier’s Probability Model: When Someone Actually Does the Math

Most debates about Jesus collapse into appeals to authority. Richard Carrier’s On the Historicity of Jesus at least does something different: it quantifies the evidence.

Using Bayesian reasoning, he argues roughly:

- about a 1 in 3 prior probability that there was a “minimal historical Jesus”– a real Jewish teacher who got executed and inspired a movement

- about 2 in 3 for a “minimal mythicist” origin– a celestial figure whose story later got historicized

Then, after weighing the actual evidence (Paul’s silence, the late Gospels, contradictions, etc.), he argues the probability of a historical Jesus drops further, to something like 1 in 12.

You don’t have to agree with his exact numbers to see the point:

- Once you treat the sources like data, not dogma, the overconfident “of course Jesus existed, you idiot” stance looks a lot less justified.

O’Neill’s Critique of Fitzgerald: Atheist vs Atheist

Tim O’Neill, an atheist historian, wrote a long piece on Fitzgerald’s Nailed and does not hold back. His basic charges:

- Fitzgerald oversells weak arguments

- cherry-picks and misuses sources

- ignores mainstream scholarship where it contradicts him

- frames mythicism as bold truth vs. “apologist cowards,” which is just another tribal narrative

When Fitzgerald responded, he didn’t do so like someone doing serious historical work. He responded like an internet keyboard warrior.

And that same ideological vibe shows up in how he talks about people in general, which I said in the beginning.

Atheism as New Orthodoxy

The more time I spend watching atheist and deconstruction spaces online, the more obvious it becomes that a lot of these folks didn’t escape religion, they just changed uniforms. They swapped their church pews for Reddit threads, pastors for science influencers, and now “logic” is their new scripture.

Ya feel me?

It’s the same emotional energy: tribal validation, purity tests–like what do you believe or think about this? And the constant hunt for heretics who dare to ask inconvenient questions.

Say something even slightly outside the approved dogma…like pointing out that evolution (calm down, Darwin disciples) still has gaps and theoretical edges we haven’t fully nailed down and suddenly the comment section becomes the Inquisition.

They defend the theory with the exact same fervor evangelicals defend the Book of Revelation.

It’s wild.

And look, I’m all for science. I’m literally the girl who reads academic papers for funsies.

But when atheists start treating evolution like a sacred cow that can’t be questioned, or acting like “reason” is this perfect, unbiased tool that magically supports all their existing beliefs… that’s not skepticism. That’s a new orthodoxy, dressed up as a freethinker.

Different vocabulary, same psychology.

Good gravy, baby— calm down.

and….here’s the uncomfortable truth a lot of atheists don’t want to hear:

Reason isn’t the savior they think it is.

French cognitive scientists Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber have spent years studying how humans actually use reason and prepare yourself because: we don’t use it the way we think. Their research shows that reason didn’t evolve to help us discover truth. It evolved to help us win arguments, protect our identities, and persuade members of our group.

In other words:

- confirmation bias isn’t a flaw

- motivated reasoning isn’t a glitch

- tribal loyalty isn’t an accident

They are features of the reasoning system.

Which is why people who worship “logic” often behave exactly like the religious communities they left… just with new vocabulary and a different set of heretics.

This is also why intellectual diversity matters so much. You cannot reason your way to truth inside an ideological monoculture. Your brain simply won’t let you. Without competing perspectives, reasoning becomes nothing more than rhetorical self-defense, a way to signal loyalty to the tribe while pretending to be above it.

John Stuart Mill understood this long before modern cognitive science confirmed it. In On Liberty, Mill argues that truth isn’t something we protect by silencing dissent. Truth emerges through friction, through the clash of differing perspectives. A community that prides itself on “rational superiority” but cannot tolerate disagreement becomes just another church with a different hymnal.

And that’s where many atheist and deconstruction spaces are now.

They haven’t transcended dogma.

They’ve recreated it. Trading one orthodoxy for another.

This isn’t just about online atheists. This is about what happens when any movement stops questioning itself.

Challenging the Mythicist Side (Without Turning It Into Another Tribe)

Let’s get honest about the mythicist world too — because every camp has its blind spots.

Tim O’Neill’s critique of David Fitzgerald wasn’t just angry rhetoric. Strip away the insults, and he raises a few legitimate issues worth taking seriously:

1. Accusation of Agenda-Driven History

O’Neill argues that Fitzgerald starts with the conclusion “Jesus didn’t exist” and works backward, much like creationists do with Genesis.

Now Fitzgerald absolutely denies this. In his own words, he didn’t go looking for mythicism; mythicism found him when he started examining the evidence. And that’s fair.

But the deeper point still stands:

The mythicist movement can get so emotionally invested in debunking Christianity that it mirrors the very dogmatism it critiques.

You see this all over atheist spaces today — endless dunking, no nuance, purity tests, and very little actual curiosity.

That’s a valid critique.

2. Amateurism and Overreach

O’Neill also accuses Fitzgerald of relying too heavily on older scholarship, making confident claims where the evidence is thin, and occasionally overstating consensus.

Again — not entirely wrong.

Fitzgerald’s book is sharp and compelling, but it’s not the cutting-edge end of mythicism anymore.

There are places where he simplifies. There are places where he speculates.

This matters because mythicism deserves better than overconfident shortcuts.

3. Fitzgerald doesn’t push far enough

And ironically, this is where I diverge from O’Neill entirely. He thinks Fitzgerald goes too far; I think Fitzgerald stops too soon.

There are areas where the mythicist case has advanced beyond Fitzgerald’s framework, and he doesn’t touch them:

• The possibility that “Paul” himself is a literary construct

Nina Livesey and other scholars argue that:

- The Pauline voice may be a 2nd-century invention.

- The letters reflect Roman rhetorical conventions, not authentic 1st-century correspondence.

- The “apostle Paul” may be a theological persona used to unify competing sects.

Fitzgerald doesn’t address this— but it’s now one of the most provocative frontiers in the field.

• The geopolitical legacy of Abrahamic supremacy

Fitzgerald critiques Christian nationalism. Great.

But he doesn’t go upstream to examine the deeper architecture:

It focuses almost exclusively on Christian excess while leaving the deeper architecture untouched: how Abrahamic identity claims themselves shape law, land, empire, and modern geopolitics.

When you zoom out, the story is not “Christian nationalism versus secular reason.”

It is competing and cooperating Abrahamic power structures, each with theological claims about chosen-ness, inheritance, land, and destiny.

Abrahamic Power Is Not Just Christian

Very few people are willing to look at the broader landscape of Abrahamic influence in American politics and global power structures. When they do not, they miss how deeply intertwined these traditions have been for over a century.

One under-discussed example is the longstanding institutional relationship between Mormonism and Judaism, particularly around shared claims to Israel and the “house of Israel.”

This is not hidden history.

In 1995, Utah Valley State College established a Center for Jewish Studies explicitly aimed at “bridging the gap between Jews and Mormons” and guiding relationships connected to Israel. One of the board members was Jack Solomon, a Jewish community leader who publicly praised the LDS Church as uniquely supportive of Judaism.

Solomon stated at the time that “there is no place in the world where the Christian community has been so supportive of the Jewish people and Judaism,” noting LDS financial and symbolic support for Jewish institutions in Utah going back to the early twentieth century.

This matters because Mormon theology explicitly claims descent from the house of Israel. Mormons do not merely admire Judaism. They see themselves as part of Israel’s continuation and restoration.

That theological framework shapes real-world alliances.

1. The Mormon Church Is a Financial Superpower

Most Americans have no idea how wealthy the LDS Church actually is.

The Mormon Church’s real estate & investment arm, Ensign Peak Advisors, was exposed in 2019 and again in 2023 for managing a secret portfolio now estimated at:

👉 $150–$200 billion

(Source: SEC filings, whistleblower leaks, Wall Street Journal)

To compare:

- PepsiCo market cap: ~$175B

- ExxonMobil (oil giant): ~$420B

- Disney: ~$160B

Meaning:

📌 The LDS Church is financially on par with Pepsi and Disney, and not far behind Big Oil.

This is not a “church.” This is an empire.

And it invests strategically:

- massive real estate acquisitions

- agricultural control

- media companies

- political lobbying

- funding influence networks

And let’s be clear:

Mormons see themselves as a literal remnant of Israel (the last tribe) destined to help rule the Earth “in the last days.”

Which brings us to…

2. Mormonism’s Quiet Partnership with the New Apostolic Reformation (NAR)

NAR is the movement behind the so-called “Seven Mountain Mandate”— the belief that Christians must seize control of:

- Government

- Education

- Media

- Arts & Entertainment

- Business

- Religion

- Family

This is the backbone of Christian nationalism and it’s far more organized than people realize. But here’s the part that never gets discussed:

Mormon elites collaborate with NAR leadership behind the scenes.

Shared goals:

- influence over U.S. political leadership

- shaping national morality laws

- preparing for a prophetic “kingdom age”

- embedding power in those seven spheres

This isn’t fringe. This is the largest religious–political coalition in the country, and yet most journalists never touch it.

3. The Ziklag Group: A $25M-Minimum Christian Power Circle

You want to talk about “elite networks”?

Meet Ziklag: an ultra-exclusive Christian organization named after King David’s biblical stronghold. Requirements for membership: a minimum net worth of $25 million Their mission?

Not charity. Not discipleship.

Influence the Seven Mountains of society at the highest levels.

Members include:

- CEOs

- hedge-fund managers

- defense contractors

- political donors

- tech founders

Including the billionaire Uihlein family, who made a fortune in office supplies, the Greens, who run Hobby Lobby, and the Wallers, who own the Jockey apparel corporation. Recipients of Ziklag’s largesse include Alliance Defending Freedom, which is the Christian legal group that led the overturning of Roe v. Wade, plus the national pro-Trump group Turning Point USA and a constellation of right-of-center advocacy groups.

AND YET…

Most people yelling about “Christian nationalism” have never even heard of Ziklag.

4. Meanwhile, Chabad-Lubavitch Has Met with Every U.S. President Since 1978

Evangelical influence isn’t the only Abrahamic power Americans ignore.

Chabad (a Hasidic cult with global reach) has:

- direct access to every U.S. president

- annual White House proclamations (“Education & Sharing Day”) explicitly honor a religious leader as a moral authority over the nation.

- a network of emissaries (shluchim) embedded in power centers around the world

This is influence, not conspiracy.

This is religious lobbying at the highest level of government, treated as unremarkable simply because the public doesn’t understand it.

See the Pattern Yet?

When people say “Christian nationalism,” they’re talking about one branch of a much older tree.

Christianity isn’t the problem. Atheism isn’t the solution.

The issue is Abrahamic supremacy: the belief that one sacred lineage has the right to rule, legislate, moralize, and define history for everyone else.

Across denominations, across continents, across political parties, the pattern is the same:

- chosen-people narratives

- divine-right entitlement

- mythic land claims

- sacred-tier influence operations

- the blending of theology with statecraft

“Groupish belief systems that justify valuing one’s group above others must be inventable.”

— Religion as Make-Believe.Exactly.

These power structures aren’t ancient relics. They’re alive, wealthy, organized, and deeply embedded in American political life. And yet we’re told to panic exclusively about MAGA Christians…

while studiously ignoring:

- Mormon financial empires

- NAR infiltration of U.S. political offices

- Zionist influence networks

- Chabad’s presidential pipeline

- elite Christian dominionist groups like Ziklag

This isn’t about blaming individuals.

It’s about naming systems. Because if we’re going to talk honestly about orthodoxy, myth, and power…

we need to talk about all of it— not just the parts that are fashionable to critique.

4. Mythicism still hasn’t grappled with empire

Most mythicist writing stops at:

“Jesus didn’t exist.”

Cool. Now what? The real question is:

HOW? How did a mythical figure become the operating system for Western civilization?

So, here’s where I actually land:

Christianity didn’t emerge from a single man.

It emerged from competing myths, political incentives, scriptural remixing, imperial needs, and evolving group identities.

And if that makes me someone who doesn’t quite fit in the Christian world, the atheist world, or the deconstruction world? Perfect. My loyalty is to the question, not the tribe. That’s exactly where I plan to stay.

That’s exactly where I plan to stay.

aaaand as always, maintain your curiosity, embrace skepticism, and keep tuning in. 🎙️🔒

Footnotes

1. Jodi Magness, Stone and Dung, Oil and Spit (Eerdmans, 2011).

Archaeologist specializing in 1st-century Judea; emphasizes that archaeology illuminates daily life, but cannot confirm Jesus’ existence or Gospel events.

2. Eric M. Meyers & Mark A. Chancey, Archaeology, the Rabbis, and Early Christianity (Baker Academic, 2012).

Shows how archaeology supports context, not Gospel narrative details.

3. Steve Mason, Josephus and the New Testament, 2nd ed. (Hendrickson, 2003).

Explains why the Testimonium Flavianum is partially or heavily interpolated and cannot serve as independent confirmation of Jesus.

4. Alice Whealey, “The Testimonium Flavianum in Syriac and Arabic,” New Testament Studies 54.4 (2008): 573–590.

Analyzes manuscript traditions showing Christian editing of Josephus.

5. Louis Feldman, “Josephus,” Anchor Bible Dictionary, vol. 3 (Yale University Press, 1992).

Standard reference summarizing scholarly consensus about the unreliable portions of Josephus’ Jesus passages.

6. Brent Shaw, “The Myth of the Neronian Persecution,” Journal of Roman Studies 105 (2015): 73–100.

Shows Tacitus likely repeats Christian stories, not archival Roman data, making him a witness to Christian belief — not Jesus’ historicity.

7. Pliny the Younger, Epistles 10.96–97.

Earliest Roman description of Christian worship; confirms Christians existed, not that Jesus did.

8. Bart D. Ehrman, Misquoting Jesus (HarperOne, 2005).

Explains why New Testament manuscripts contain thousands of variations, with no originals surviving.

9. Dennis R. MacDonald, The Homeric Epics and the Gospel of Mark (Yale University Press, 2000).

Argues Mark intentionally modeled episodes on Homeric motifs — supporting literary construction rather than eyewitness reporting.

10. Attridge, Harold W., The Epistle to the Hebrews (Hermeneia Commentary Series).

Shows how Hebrews relies on celestial priesthood imagery and makes no connection to a recent earthly Jesus, even when opportunities are obvious.

11. Earl Doherty, The Jesus Puzzle (1999).

Early mythicist argument emphasizing the epistles’ lack of biographical Jesus data.

12. Richard Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus (Sheffield Phoenix, 2014).

Presents a Bayesian model estimating mythicist origins as more probable than historicity.

13. Richard Carrier, Proving History (Prometheus, 2012).

Explains the historical method he uses for evaluating Jesus traditions.

14. Paula Fredriksen, From Jesus to Christ (Yale University Press, 2000).

Demonstrates the pluralism and fragmentation within earliest Christianity.

15. Burton Mack, The Christian Myth: Origins, Logic, and Legacy (Continuum, 2006).

Describes the emergence of various Jesus traditions as literary and theological constructions.

16. Clayton N. Jefford, The Didache (Fortress Press).

Analyzes early church manual revealing “wandering prophets,” factionalism, and market-style competition among early Jesus groups.

17. Catherine Nixey, The Darkening Age (Macmillan, 2017).

Documents the destruction of pagan culture under Christian imperial dominance.

18. Charles Freeman, The Closing of the Western Mind (Vintage, 2005).

Explores how Christian orthodoxy displaced classical philosophy.

19. Ramsay MacMullen, Christianizing the Roman Empire (Yale University Press, 1984).

Shows Christianity expanded primarily through imperial power, incentives, and legislation, not mass persuasion.

20. H.A. Drake, Constantine and the Bishops (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002).

Outlines Constantine’s political use of Christianity and the shift toward enforced orthodoxy.

21. Peter Brown, The Rise of Western Christendom (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013).

Provides context for how Christianity overtook the Roman religious landscape.

22. Neil Van Leeuwen, “Religious Credence Is Not Factual Belief,” Cognition 133 (2014): 698–715.

Explains why religious commitments behave like identity markers, not evidence-responsive beliefs.

23. Whitney Phillips, This Is Why We Can’t Have Nice Things (MIT Press, 2015).

Useful for understanding modern online purity culture dynamics, relevant to atheist-internet behavior discussed in your commentary section.

24. Joseph Reagle, Reading the Comments (MIT Press, 2015).

Analyzes comment-section behavior and ideological enforcement online.

25. Tim O’Neill, “Easter, the Existence of Jesus, and Dave Fitzgerald,” History for Atheists (2017).

Atheist historian critiquing Fitzgerald’s methodological errors, exaggerated claims, and misuse of sources.

26. Raphael Lataster, Questioning the Historicity of Jesus (Brill, 2019).

Secular academic arguing mythicism is plausible but insisting on higher methodological rigor than many popularizers use.

27. Richard Carrier, various blog critiques of Fitzgerald (2012–2019).

Carrier agrees with mythicism but critiques Fitzgerald for overstatement and inadequate source control.