Between Liberation and Collapse: Why We Need to Talk About the Middle Path

Welcome back to Taste Test Thursdays, where we explore health, culture, belief, and everything in between. I’m your host, Megan Leigh and today, we’re asking a question that’s bound to make someone uncomfortable:

What if the very institutions we tore down as oppressive… were also protecting us?

We live in a time of extremes. On one side, you’ve got Quiverfull-style fundamentalists preaching hyper-fertility and wifely submission like it’s the only antidote to modern decay. On the other, we’ve got a postmodern buffet of “do what you want, gender is a vibe, all structures are violence.”

And if you’re like me—having navigated the high-control religion pipeline but also come out the other side—you might be wondering…

“Wait… does anyone believe in guardrails anymore?”

Because spoiler: freedom without form becomes chaos. And chaos isn’t empowering. It’s destabilizing.

I truly believe that structure and boundaries can actually serve a purpose—especially when it comes to sex, gender, and human flourishing.

This isn’t a call to go backward. It’s a call to pause, zoom out, and ask: what’s been lost in our so-called progress? Let’s dig in.

The Panic Playbook

This past summer, the media went full apocalyptic. You couldn’t scroll, stream, or tune in without hearing it: Christian nationalism is taking over. Project 2025 is a fascist manifesto. Trump is a theocratic threat to democracy itself. The narrative was everywhere—breathless Substacks, viral TikToks, and cable news countdowns to Gilead.

But while progressives were busy hallucinating handmaids and framing every Republican vote as the end of America, they were also helping cover up the biggest political scandal since Watergate: Biden’s cognitive decline.

This blog isn’t a right-wing defense or a leftist takedown. It’s a wake-up call. Because authoritarian creep doesn’t wear just one team’s jersey. If we’re serious about resisting tyranny, we need to stop fearmongering about theocracy and start interrogating the power grabs happening under our own banners—especially the ones cloaked in compassion, inclusion, and “equity.”

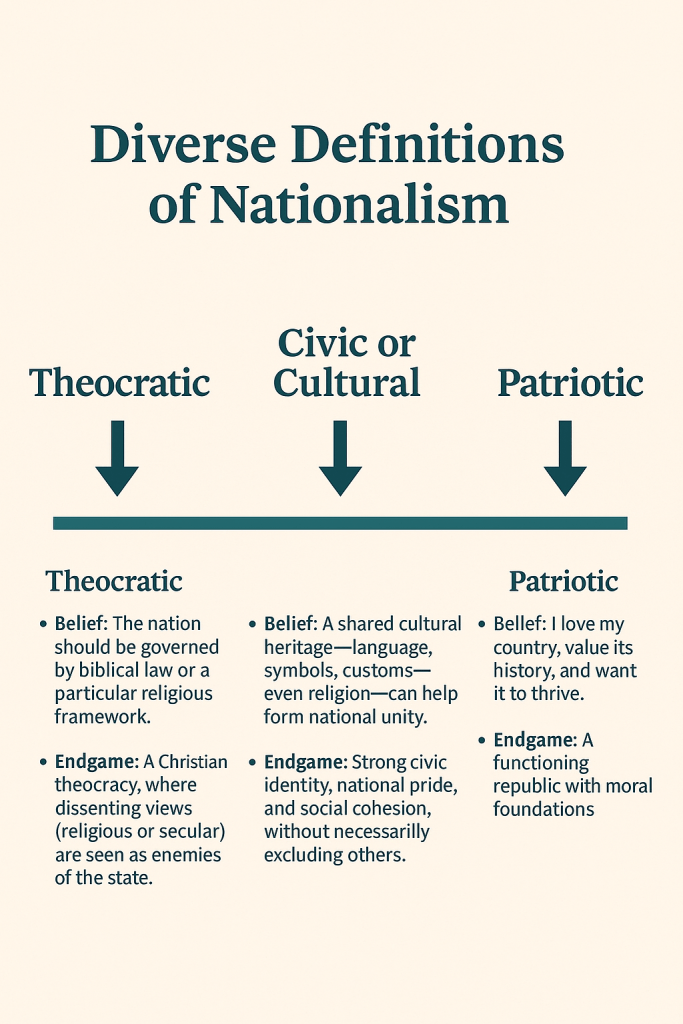

Not All “Christian Nationalism” Is the Same—Let’s Break It Down

The term “nationalism” gets thrown around a lot, but it actually has different meanings:

🔸 1. The Theocratic Extreme

This is the version everyone fears—and with good reason.

- Belief: Government should follow biblical law.

- Goal: A Christian theocracy where dissent is treated as rebellion.

- Associated with: Christian Reconstructionism, Dominionism, and groups hostile to pluralism.

📍 Reality: This is fringe. Most evangelicals don’t support this, but it’s the go-to boogeyman in media and deconstruction circles.

🔸 2. Civic or Cultural Nationalism

More common, less scary.

- Belief: Shared culture—language, customs, even religion—can create unity.

- Goal: Strong national identity and cohesion, not exclusion.

- Seen in: France’s secularism, Japan’s cultural pride, and even Fourth of July BBQs.

📍 Reality: This is where most “Christian nationalists” actually land. They believe in the U.S.’s Christian roots and want to preserve those values—not enforce a theocracy.

🔸 3. Patriotism (Often Mislabeled as Nationalism)

Here’s where it gets absurd.

- Belief: Loving your country and its traditions.

- Goal: A moral, thriving republic.

📍 Reality: Critics lump this in with extremism to discredit conservatives, centrists, or people of faith.

Why It Matters

Lumping everyone—from flag-waving moderates to dominionist hardliners—into one “Christian nationalist” category fuels moral panic. It shuts down real dialogue and replaces nuance with hysteria.

You can:

✅ Love your country

✅ Value strong families

✅ Want morality in public life

…without wanting a theocracy.

Let’s Define the Terms Critics Confuse:

- Dominionism: A fringe movement pushing for Christian control of civic life. Exists, but not mainstream.

- Quiverfull: Ultra-niche belief in having as many kids as possible for religious reasons. Rare and extreme.

- Christian Nationalism: Belief that the U.S. has a Christian identity that should shape culture and law. Vague, often misapplied.

And What It Isn’t:

- Pro-natalism: A global concern over falling birth rates—not just a religious thing.

- Conservative Feminism: Belief in empowerment through family and tradition. Dismissing it as brainwashing is anti-feminist.

- Family Values: Often demonized, but for many, it just means prioritizing marriage, kids, and legacy.

Not all traditionalism is fascism.

Not all progressivism is liberation.

Let’s keep the conversation honest.

Hillary’s “Handmaid” Moment

Hilary Clinton🎧 “Well, first of all, don’t be a handmaiden to the patriarchy. Which kind of eliminates every woman on the other side of the aisle, except for very few. First, we have to get there, and it is obviously so much harder than it should be. So, if a woman runs who I think would be a good president, as I thought Kamala Harris would be, and as I knew I would be, I will support that woman.”

This quote from Hillary Clinton caused predictable outrage—but what’s more disturbing than the clip is the sentiment behind it.

In one breath, she managed to dismiss millions of women—mothers, caretakers, homemakers, conservative politicians, religious traditionalists—as unwitting slaves to male domination. Clinton doesn’t leave room for the idea that a woman might freely choose to prioritize home, faith, or family—not because she’s brainwashed, but because she’s pragmatic, thoughtful, and in tune with her own values.

To Clinton, there’s one legitimate type of woman in politics: the woman who governs like Hillary Clinton.

This framework—that conservative, traditional, or religious women are “handmaidens”—isn’t new. It’s a familiar talking point in progressive circles. And lately, it’s been weaponized even more boldly, as Clinton revealed in another recent statement:

“…blatant effort to basically send a message, most exemplified by Vance and Musk and others, that, you know, what we really need from you women are more children. And what that really means is you should go back to doing what you were born to do, which is to produce more children. So this is another performance about concerns they allegedly have for family life. Return to the family, the nuclear family. Return to being a Christian nation. Return to, you know, producing a lot of children, which is sort of odd because the people who produce the most children in our country are immigrants and they want to deport them, so none of this adds up.”

This is where modern feminism loses its plot. If liberation only counts when women make certain kinds of choices, it’s not about freedom then.

The Pro-Natalism Panic—and the Projection Problem

🎧 “Although the Quiverfull formal life isn’t necessarily being preached, many of the underlying theological and practical assumptions are elevated… and now, you know, they’re in the White House.”

– Emily Hunter McGowin, guest on In the Church Library podcast with Kelsey Kramer McGinnis and Marissa Franks Burt

There’s a subtle but dangerous trend happening in the deconstruction space: lumping all traditional Christian views of family into the Quiverfull/Dominionist bucket.

In a recent episode of In the Church Library, the hosts and guest reflected on the rise of pro-natalist ideas and Christian influence in politics. Marissa asks whether the ideology behind the Quiverfull movement might be getting a new rebrand—and Emily responds with what sounds like a chilling observation: echoes of that movement are now in the White House.

But let’s pause.

❗ The Quiverfull movement is real—but it’s fringe. It’s not representative of all evangelicals, conservatives, or even Christian pro-family thinking.

Yet increasingly, any policy or belief that values marriage, child-rearing, or generational stability gets painted with that same extremist brush. This is where projection replaces analysis.

Take J.D. Vance, often scapegoated in these conversations. He’s frequently accused of trying to turn America into Gilead—even though he has three children, supports working-class families, and hasn’t once called for a theocracy. His concern? America’s birthrate is in freefall.

That’s not theocracy. That’s math.

Pro-natalism isn’t about forcing women to give birth. It’s about grappling with a demographic time bomb. Countries like South Korea, Hungary, and Italy are facing societal collapse because too few people are having children. This isn’t moral panic—it’s math.

Even secular thinkers are sounding the alarm:

Lyman Stone, an economist and demographer, emphasizes: “Lower fertility rates are harbingers of lower economic growth, less innovation, less entrepreneurship, a weakened global position, any number of factors… But for me, the thing I worry about most is just disappointment. That is a society where most people grow old alone with little family around them, even though they wanted a family.”

Paul Morland, a British demographer, warns: “We’ve never seen anything like this kind of population decline before. The Black Death wiped out perhaps a third of Europe, but we’ve never seen an inverted population pyramid like the one we have today. I can’t see a way out of this beyond the supposedly crazy notion that people should try to have more kids.”

We have to be able to separate structure from subjugation. There’s a world of difference between saying “families matter” and forcing women into barefoot-and-pregnant obedience.

When we flatten every traditional idea into a fundamentalist threat, we not only lose clarity—we alienate people who are genuinely seeking meaning, stability, and community in a fragmented culture.

If we want to be intellectually honest, we must distinguish:

- Extremism vs. Order

- Oppression vs. Structure

- Religious Tyranny vs. Social Cohesion

And we should probably stop pretending that every road leads to the Handmaid’s Tale.

Protective Powers: What Louise Perry and Joan Brumberg Reveal About Institutions

Let’s talk about The Case Against the Sexual Revolution by Louise Perry. Perry is a secular feminist. She’s not nostalgic for 1950s housewife culture—but she is asking: what did we actually get from the sexual revolution?

Here’s her mic-drop:

“The new sexual culture didn’t liberate women. It just asked them to participate in their own objectification with a smile.”

We built an entire culture around the idea that as long as it’s consensual, it’s empowering. But Perry argues that consent—without wisdom, without boundaries, without institutional protection—leaves women wide open to harm.

She points to:

- Porn culture

- Casual hookups

- The normalization of sexual aggression and coercion in dating

These aren’t signs of liberation—they’re signs of a society that privatized female suffering and told us to smile through it.

Perry doesn’t say “go full tradwife.” But she does say maybe marriage, sexual restraint, and even modesty functioned as protective constraints—not just patriarchal tools of oppression.

We traded one form of pressure (be pure, stay home) for another (be hot, work hard, never need a man). Neither version asked what women actually want.

Now flip over to The Body Project by Joan Jacobs Brumberg. This one blew my mind.

She traces how, a century ago, girls were taught to cultivate inner character: honesty, kindness, self-control.

By the late 20th century? That inner moral development had been replaced by bodily self-surveillance: thigh gaps, clear skin, flat stomachs. Girls now focus on looking good, not being good.

She writes:

“The body has become the primary expression of self for teenage girls.”

Think about that. We went from teaching virtue to teaching girls how to market themselves. We told them they were free—and then handed them Instagram and said, “Good luck.”

So again, maybe some of those “oppressive” structures were also serving as cultural scaffolding. Not perfect. Not painless. But they gave young people—especially girls—a script that wasn’t just: “Be hot, be available, and don’t catch feelings.”

Brumberg isn’t saying go back to corsets and courtship. But she is saying we’ve lost our moral imagination. We gave up teaching self-restraint and purpose and replaced it with branding. With body projects. And now we wonder why depression and anxiety are through the roof??

We dive deeper into these subjects in these two podcasts:

Why the Fear Feels Real—And Why It’s Still Misguided

Look, I get it.

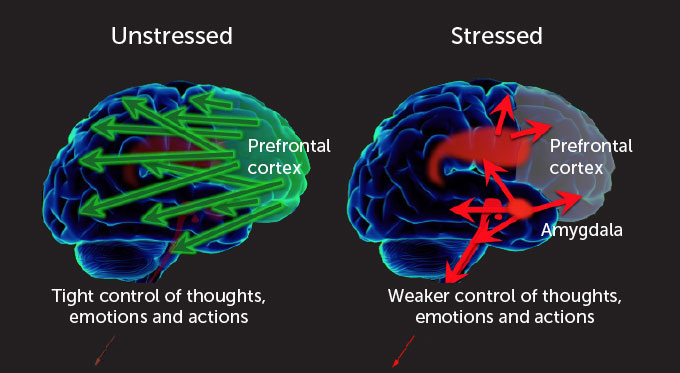

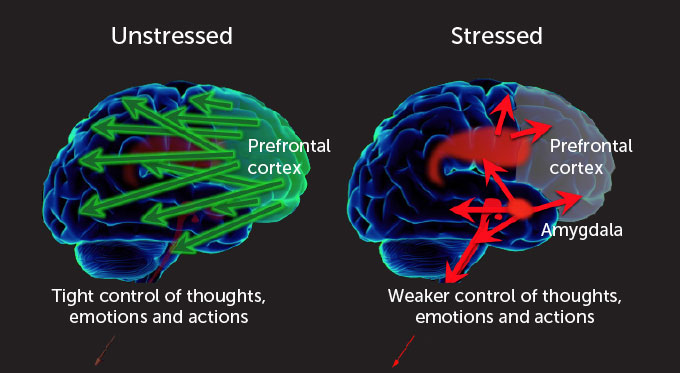

If you’ve escaped religious trauma, purity culture, or spiritual abuse, the sight of a political figure talking about motherhood as a virtue can feel like a threat. Your nervous system registers it as a return to oppression. The media confirms your panic. And suddenly, a call for demographic survival starts sounding like a demand for forced birth.

But your trauma doesn’t make every policy that triggers you authoritarian. It just means you need to slow down and check the data.

Because ironically, the real threats to bodily autonomy and family structure? They might not be coming from traditionalists at all.

🏛 The Progressive Power Grab You’re Not Supposed to Question

Another frustrating comment made by Kelsey Kramer McGinnis in a recent podcast was the need to “decenter nuclear families” and the dismissal of concerns about an “attack on nuclear families” as mere panic. But here’s the thing—this fear isn’t fabricated. It’s not fringe. It’s rooted in observable cultural trends and policy shifts. You can’t just wave it away with smug academic detachment.

Whether you support the traditional family structure or not, the erosion of it has real consequences—especially for children, social stability, and intergenerational resilience. Calling that out isn’t fearmongering. It’s an invitation to discuss the stakes honestly.

Let’s set the record straight: The desire to shape culture, laws, and education systems is not the sole domain of religious conservatives. Dominionist Christians aren’t the only ones with blueprints for a theocratic society. Progressive activists also seek to remake the world in their image—one institution at a time.

This isn’t a right-wing “whataboutism.” It’s an honest observation about how ideological movements—regardless of political lean—operate when they gain influence.

Let’s take a look at what this looks like on both ends of the spectrum:

🏛 Dominionism (Far-Right Christian Nationalism)

Core Belief: Christians are mandated by God to bring every area of life—government, education, business—under biblical authority.

Tactics:

- Homeschool curricula promoting biblical literalism and creationism.

- Campaigns for Christian prayer in public schools or Ten Commandments monuments in courthouses.

- Promoting the idea that America was founded as a Christian nation and must return to those roots.

- Electing openly Christian lawmakers with the explicit goal of reshaping law and public policy to reflect “biblical values.”

- Supporting the Quiverfull movement, which encourages large families to “outbreed the left” and raise up “arrows for God’s army.”

📘 Progressive Institutional Capture (Far-Left Activism)

Core Belief: Society must be dismantled and rebuilt to eliminate systemic oppression, centering race, gender, and identity as primary moral lenses.

Tactics:

- Embedding DEI (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion) frameworks into public schools, universities, and corporate policy.

- Redefining gender and sex in school curricula while often sidelining parental input or community values.

- Elevating “lived experience” over objective standards in hiring, curriculum design, and academic research.

- Weaponizing social media and institutional policies to punish dissenting views (labeling them as “harmful,” “unsafe,” or “hateful”).

- Using activist lingo to obscure government overreach (“gender-affirming care” vs. irreversible medical intervention for minors).

🔄 Shared Behaviors: The Race to Capture Institutions

Despite their stark differences in values, both dominionists and far-left activists behave in eerily similar ways:

- They seek cultural dominance through schools, law, media, and public policy.

- They view their moral framework as not just legitimate but necessary for a just society.

- They suppress dissent by pathologizing disagreement—branding critics as “anti-Christian,” “bigoted,” “transphobic,” “groomers,” or “domestic extremists.”

The battleground is no longer just the ballot box. It’s the school board meeting. The state legislature. The HR department. The university curriculum. The TikTok algorithm.

Colorado’s HB25-1312 — The “Kelly Loving Act”

Signed in May 2025, this law expands protections for transgender individuals. Fine on the surface. But here’s the fine print:

- It redefines coercive control to include misgendering and deadnaming.

- In custody cases, a parent who refuses to affirm a child’s gender identity could now be framed as abusive—even if that child is a minor in the midst of rapid-onset gender dysphoria.

Is it protecting kids? Or is it using identity to override parental rights?

Washington State’s HB 1296

This bill guts the Parents’ Bill of Rights (which was approved by voters via Initiative 2081). It:

- Eliminates mandatory parental access to children’s health records (including mental health).

- Enshrines gender identity and sexual orientation in a new “Student Bill of Rights.”

- Allows state-level monitoring of school boards that don’t comply.

And the cherry on top? It was passed with an emergency clause so it would take effect immediately, bypassing normal legislative scrutiny.

This isn’t some abstract culture war. These are real laws, passed in real states, stripping real parents of their authority.

A Marxist Framework Masquerading as Compassion

Some of these changes echo critical theory more than constitutional liberty.

Historically, Marxist and Maoist ideologies viewed the family unit as an oppressive structure that needed dismantling. Parental authority was often seen as an extension of capitalist control. In its place? State-affirmed loyalty, reeducation, and ideological uniformity.

Now, it’s not happening with red stars and gulags—it’s happening through rainbow flags and DEI seminars. But the power dynamics are the same:

The family becomes secondary to the state.

Dissent becomes dangerous.

Disagreement becomes “violence.”

This is how authoritarianism creeps in—wrapped in the language of safety and inclusion.

What Real Theocracy Looks Like

If you need a reality check, read Yasmine Mohammed’s Unveiled. Raised in a fundamentalist Muslim home, where women had no autonomy, no basic rights, and no freedom. She was forced into hijab at age 9, married off to an al-Qaeda operative, and beaten for asking questions. Women cannot see a doctor without a male guardian, they are forced to cover every inch of their bodies and are denied access to education and even the right to drive. That’s theocracy. That is TRUE oppression.

Now contrast that with the freedom that women enjoy in the West today. In modern America, women have more rights and freedoms than at any point in history. Women can run around naked at Pride parades, express their sexuality however they choose, and redefine what it means to be a woman altogether. The very idea of a “dystopia” here is laughable when we consider the actual freedom women in the West enjoy.

Yet, despite these freedoms, many liberal women still cry oppression. They whine about having to pay for their student loans, birth control or endure debates over abortion restrictions. This level of cognitive dissonance—claiming victimhood while living in unprecedented freedom—is a slap in the face to women who actually suffer under real patriarchal oppression.

What’s even more Orwellian is how the left, in its quest for inclusivity and justice, is actively stripping others of their freedoms. They preach about fighting for freedom of speech while canceling anyone who disagrees with them. They claim to be champions of equality while weaponizing institutions to enforce ideological conformity.

Bottom line: If you think Elon Musk tweeting about birth rates is the same as what Yasmine went through? You’ve lost perspective.

To revisit my conversation with Yasmine:

Fear Isn’t Feminism

If your feminism can’t handle dissent, it was never liberation—it was just a prettier cage.

We have to stop mistaking fear for wisdom. We have to stop confusing criticism with violence. And we absolutely must stop handing our power over to ideologies that infantilize us in the name of compassion.

Let’s be clear: Gilead isn’t coming. But if we’re not careful, something just as destructive might.

A world where parents are powerless.

Where biology is negotiable but ideology is law.

Where compliance is the only virtue, and questions are a crime.

The Courage to Be Honest

What I’m suggesting isn’t fashionable. It doesn’t fit neatly in a progressive or conservative box. But I’m tired of those boxes.

I’ve lived in Portland’s secular utopia and inside a high-control religious environment. I’ve seen how each side distorts truth in the name of “freedom” or “righteousness.”

But what if true liberation is found in the tension between the two?

The most revolutionary thing we can do today is refuse to become an extremist.

Not because we’re afraid.

Not because we’re fence-sitters.

But because we believe there’s a better way—one that honors the past without being imprisoned by it and faces the future with clear eyes and moral courage.

Maintain your curiosity, embrace skepticism, and keep tuning in. 🎙️🔒

— Megan Leigh

📚 Source List for Blog Post

1. Hillary Clinton Quotes

- Quote 1 (on being a “handmaiden to the patriarchy”):

[Reference: “Defending Democracy” podcast with historian Heather Cox Richardson, May 2024]

No official transcript published — you’re using a direct audio clip for this one. - Quote 2 (on pro-natalism and immigration):

[Source: Same podcast — “Defending Democracy” with Heather Cox Richardson, 2024]

Partial reference via The Independent article

2. Louise Perry

- The Case Against the Sexual Revolution

Publisher link

3. Mary Harrington

- Feminism Against Progress

Publisher link

4. Demographer Paul Morland

- Quote source:

Spiked interview – “We have never seen our populations fall like this before” - Book reference: The Human Tide: How Population Shaped the Modern World

Publisher link

5. Lyman Stone

- Quote source:

NC Family podcast interview – “How to Fix Our Falling Fertility Rate” - Substack: In a State of Migration

6. Dominionism & Quiverfull Movement

7. Recent Legislation Affecting Parental Rights

- Colorado House Bill 25-1312 (Kelly Loving Act)

Official Colorado Bill Summary - Washington State House Bill 1296 (2025)

WA Legislature Bill Info – HB 1296 - Parents’ Bill of Rights (Initiative 2081, WA)

WA State Initiative 2081 Summary