What Women Were Never Told About Weight, Aging, and Control

The Science They Never Told Us

This is the first episode of 2026, and I wanted to start the year by slowing things down, getting a bit personal instead of chasing the latest talking points.

At the end of last year, I spent time reading a few books that genuinely stopped me in my tracks. Not because they offered a new diet or a new protocol, but because they challenged something much deeper: the story we’ve been told about discipline, control, and women’s bodies.

There is a reason women’s bodies change across the lifespan. And it has very little to do with willpower, discipline, or personal failure.

In Why Women Need Fat, evolutionary biologists William Lassek and Steven Gaulin make the case that most modern conversations about women’s weight are fundamentally misinformed. Not because women are doing something wrong, but because we’ve built our expectations on a misunderstanding of what female bodies are actually designed to do.

A major part of their argument focuses on how industrialization radically altered the balance of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids in the modern food supply, particularly through seed oils and ultra-processed foods. They make a compelling case that this shift plays a role in rising obesity and metabolic dysfunction at the population level.

I agree that this imbalance matters, and it’s a topic that deserves its own full episode. At the same time, it does not explain every woman’s story. Diet composition can influence metabolism, but it cannot override prolonged stress, illness, hormonal disruption, nervous system dysregulation, or years of restriction. In my own case, omega-6 intake outside of naturally occurring sources is relatively low and does not account for the changes I’ve experienced. That matters, because it reminds us that biology is layered. No single variable explains a complex adaptive system.

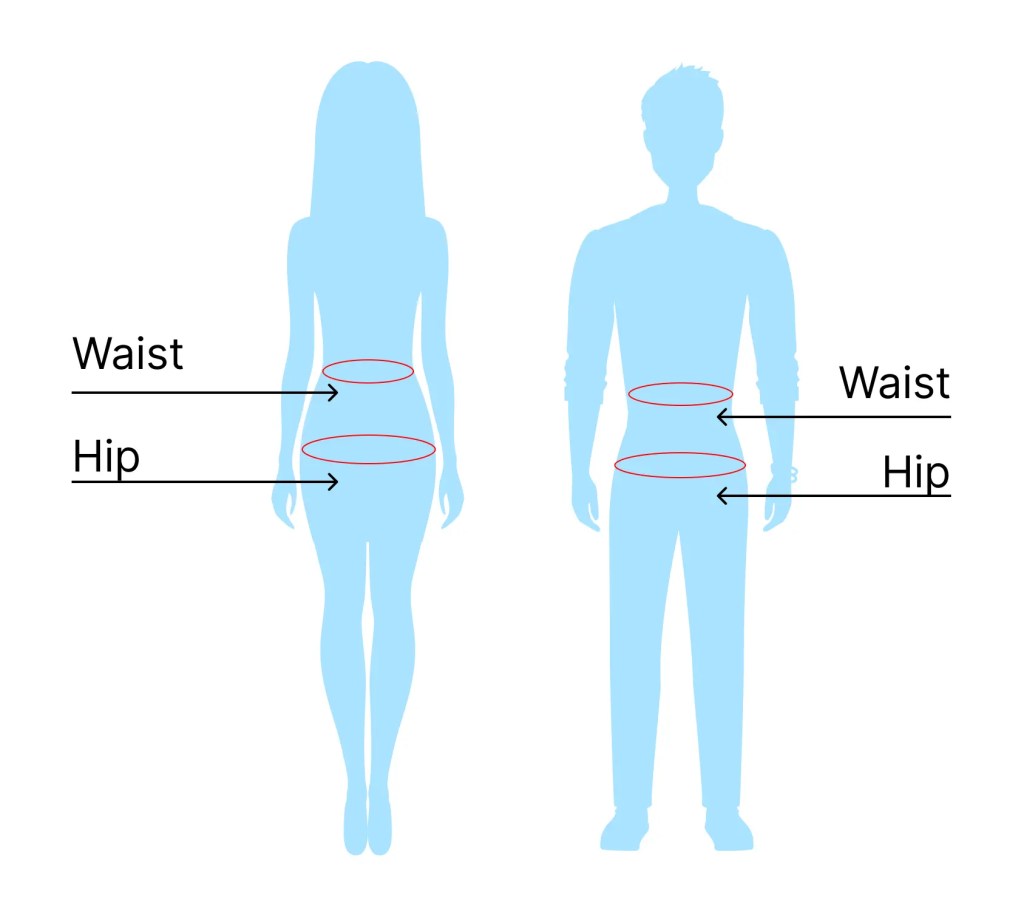

One of the most important ideas in the book is that fat distribution matters more than fat quantity.

Women do not store fat the same way men do. A significant portion of female body fat is stored in the hips and thighs, known as gluteofemoral fat. This fat is metabolically distinct from abdominal or visceral fat. It is more stable, less inflammatory, and relatively enriched in long-chain fatty acids, including DHA, which plays a key role in fetal brain development.

From an evolutionary standpoint, this makes sense. Human infants are born with unusually large, energy-hungry brains. Women evolved to carry nutritional reserves that could support pregnancy and lactation, even during times of scarcity. In that context, having fat on your lower body was not a flaw or a failure. It was insurance.

From this perspective, fat is not excess energy. It is deferred intelligence, stored in anticipation of future need. This is where waist-to-hip ratio enters the conversation.

Across cultures and historical periods, a lower waist-to-hip ratio in women has been associated with reproductive health, metabolic resilience, and successful pregnancies. This is not about thinness, aesthetics, or moral worth. It is about fat function, not fat fear, and about how different tissues behave metabolically inside the body. It is about where fat is stored and how it functions.

And in today’s modern culture we have lost that distinction.

Instead of asking what kind of fat a woman carries, we became obsessed with how much. Instead of understanding fat as tissue with purpose, we turned it into a moral scoreboard. Hips became a problem. Thighs became something to shrink. Curves became something to discipline.

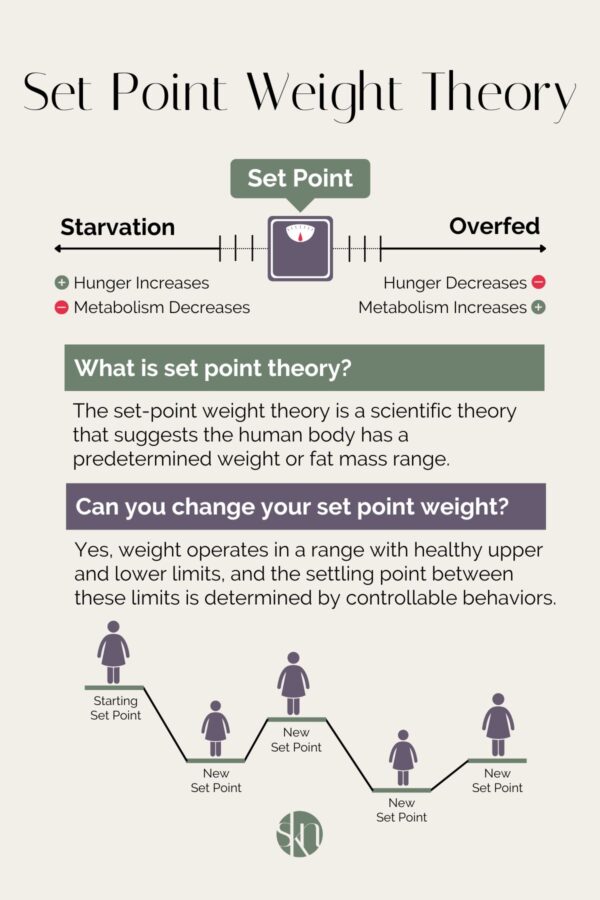

Another central idea in Why Women Need Fat is biological set point.

The authors argue that women’s bodies tend to defend a natural weight range when adequately nourished and not under chronic stress. When women remain below that range through restriction, over-exercise, or prolonged under-fueling, the body does not interpret that as success. It interprets it as threat.

Over time, the body adapts, not out of defiance, but out of protection.

Metabolism slows. Hunger and fullness cues become unreliable. Hormonal systems compensate. When the pressure finally eases, weight often rebounds, sometimes beyond where it started, because the body is trying to restore safety.

From this perspective, midlife weight gain, post-illness weight gain, or weight gain after years of restriction is not mysterious. It is not rebellion. It is regulation.

None of this is taught to women.

Instead, we are told that if our bodies change, we failed. That aging is optional. That discipline and botox should override biology. That the number on the scale tells the whole story.

So, before we talk about culture, family, trauma, or personal experience, this matters:

Women’s bodies are not designed to stay static.

They are designed to adapt.

Once you understand that, everything else in this conversation changes.

Why the Body Became the Battlefield

This is where historian Joan Jacobs Brumberg’s work in The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls, provides essential context, but it requires some precision.

Girls have not always been free from shame. Shame itself is not new. What has changed is what women are taught to be ashamed of, and how that shame operates in daily life.

Brumberg asks a question that still feels unresolved today:

Why is the body still a girl’s nemesis? Shouldn’t sexually liberated girls feel better about themselves than their corseted counterparts a century ago?

Based on extensive historical research, including diaries written by American girls from the 1830s through the 1990s, Brumberg shows that although girls today enjoy more formal freedoms and opportunities, they are also under more pressure and at greater psychological risk. This is due to a unique convergence of biological vulnerability and cultural forces that turned the adolescent female body into a central site of social meaning during the twentieth century.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, girls did not typically grow up fixated on thinness, calorie control, or constant appearance monitoring. Their diaries were not filled with measurements or food rules. Instead, they wrote primarily about character, self-restraint, moral development, relationships, and their roles within family and community.

One 1892 diary entry reads:

“Resolved, not to talk about myself or feelings. To think before speaking. To work seriously. To be self-restrained in conversation and in actions. Not to let my thoughts wander. To be dignified. Interest myself more in others.”

In earlier eras, female shame was more often tied to behavior, sexuality, obedience, and virtue. The body mattered, but primarily as a moral symbol rather than an aesthetic project requiring constant surveillance and correction.

That changed dramatically in the twentieth century.

Brumberg documents how the mother-daughter connection loosened, particularly around menstruation, sexuality, and bodily knowledge. Where female relatives and mentors once guided girls through these transitions, doctors, advertisers, popular media, and scientific authority increasingly stepped in to fill that role.

At the same time, mass media, advertising, film, and medicalized beauty standards created a new and increasingly exacting ideal of physical perfection. Changing norms around intimacy and sexuality also shifted the meaning of virginity, turning it from a central moral value into an outdated or irrelevant one. What replaced it was not freedom from scrutiny, but a different kind of pressure altogether.

By the late twentieth century, girls were increasingly taught that their bodies were not merely something they inhabited, but something they were responsible for perfecting.

A 1982 diary entry captures this shift starkly:

“I will try to make myself better in any way I possibly can with the help of my budget and baby-sitting money. I will lose weight, get new lenses, already got a new haircut, good makeup, new clothes and accessories.”

What changed was not the presence of shame, but its location. Shame moved inward.

Rather than being externally enforced through rules and prohibitions, it became self-policed. Girls were taught to monitor themselves constantly, to evaluate their bodies from the outside, and to treat appearance as the primary expression of identity and worth.

Brumberg is explicit on this point. The fact that American girls now make their bodies their central project is not an accident or a cultural curiosity. It is a symptom of historical changes that are only beginning to be fully understood.

This is where more recent work, such as Louise Perry’s The Case Against the Sexual Revolution, helps extend Brumberg’s analysis into the present moment. Perry argues that while sexual liberation promised autonomy and empowerment, it often left young women navigating powerful biological and emotional realities without the social structures that once offered protection, guidance, or meaning. In that vacuum, the body became one of the few remaining sites where control still seemed possible.

The result is a paradox. Girls are freer in theory, yet more burdened in practice. The body, once shaped by communal norms and shared female knowledge, becomes a solitary project, managed under intense cultural pressure and constant comparison.

For many girls, this self-surveillance does not begin with magazines or social media. It begins at home, absorbed through tone, comments, and modeling from the women closest to them.

Brumberg argues that body dissatisfaction is often transmitted from mother to daughter, not out of cruelty, but because those mothers inherited the same aesthetic anxieties. Over time, body shame becomes a family inheritance, passed down quietly and persistently.

Some mothers transmit it subtly.

Others do it bluntly.

This matters not because my experience is unique, but because it illustrates what happens when a body shaped by restriction, stress, and cultural pressure is asked to perform indefinitely. Personal stories are often dismissed as anecdotal, but they are where biological theory meets lived reality.

If you want to dive deeper into this topic:

Where It All Began: The Messages That Shape Us

I grew up in a household where my body was not simply noticed. It was scrutinized, compared, and commented on. Comments like that do not fade with time. They shape how you see yourself in mirrors and photographs. They teach you that your body must be managed and monitored. They plant the belief that staying small is the price of safety.

So, I grew up believing that if I could control my body well enough, I could avoid humiliation. I could avoid becoming the punchline. I could avoid being seen in the wrong way.

For a while, I turned that fear into discipline.

The Years Before the Collapse: A Lifetime of Restriction and Survival

Food never felt simple for me. Long before bodybuilding, chronic pain, or COVID, I carried a strained relationship with eating. Growing up in a near constant state of anxiety meant that hunger cues often felt unpredictable. Eating was something to plan around or push through. It rarely felt intuitive or easy.

Because of this, I experimented with diets that replaced real meals with cereal or shakes. I followed plans like the Special K diet. I relied on Carnation Instant Breakfast instead of full meals. My protein intake was low. My fear of gaining weight was high. Restriction became familiar.

In college, I became a strict vegetarian out of compassion for animals, but I did not understand how to meet my nutritional needs. I was studying dietetics and earning personal training certifications while running frequently and using exercise as a way to maintain control. From the outside, I looked disciplined. Internally, my relationship with food and exercise remained tense and inconsistent.

Later, I became involved in a meal-replacement program through an MLM. I replaced two meals a day with shakes and practiced intermittent fasting framed as “cleanse days.” In hindsight, this was structured under-eating presented as wellness. It fit seamlessly into patterns I had lived in for years.

Eating often felt overwhelming. Cooking felt like a hurdle. Certain textures bothered me. My appetite felt fragile and unreliable. This sensory sensitivity existed long before the parosmia that would come years later. From early on, food was shaped by stress rather than nourishment.

During this entire period, I was also on hormonal birth control, first the NuvaRing and later the Mirena IUD, for nearly a decade. Long-term hormonal modulation can influence mood, inflammation, appetite, and weight distribution. It added another layer of complexity to a system already under strain.

Looking back, I can see that my teens and twenties were marked by near constant restriction. Restriction felt normal. Thriving did not.

The book Why Women Need Fat discusses the idea of a biological weight “set point,” the range a body tends to return to when conditions are stable and adequately nourished. I now understand that I remained below my natural set point for years through force rather than balance. My biology never experienced consistency or safety.

This was the landscape I carried into my thirties.

The Body I Built and the Body That Broke

By the time I entered the bodybuilding world in 2017 and 2018, I already had years of chronic under-eating, over-exercising, and nutrient gaps behind me. Bodybuilding did not create my issues. It amplified them.

I competed in four shows. People admired the discipline and the physique. Internally, my body was weakening. I was overtraining and undereating. By 2019, my immune system began to fail. I developed severe canker sores, sometimes twenty or more at once. I started noticing weight-loss resistance. Everything I had done in the past, was no longer working. On my thirty-fifth birthday, I got shingles. My energy crashed. My emotional bandwidth narrowed. My body was asking for rest, but I did not know how to slow down.

Dive deeper into my body building journey here:

Around this time, I was also navigating eating disorder recovery. Learning how to eat without panic or rigid control was emotionally exhausting even under ideal circumstances… but little did I know things were about to take a massive turn for the worst.

COVID, Sensory Loss, and the Unraveling of Appetite

After getting sick with the ‘vid late 2020, everything shifted again. I developed parosmia, a smell and taste distortion that made many foods taste rotten or chemical. Protein and cooked foods often tasted spoiled. Herbs smelled like artificial chemical. Eating became distressing and, at times, impossible.

My appetite dropped significantly. There were periods where my intake was very low, yet my weight continued to rise. This is not uncommon following illness or prolonged stress. The body often shifts into energy conservation, prioritizing survival overweight regulation.

Weight gain became another source of grief. Roughly thirty pounds over the next five years. I feel embarrassed and avoid photographs. I often worry about how others will perceive me.

If this experience resonates, it is important to say this clearly: your body is not betraying you. It is responding to stress, illness, and prolonged strain in the way bodies are designed to respond.

Why Women’s Bodies Adapt Instead of “Bounce Back”

When years of restriction, intense exercise, chronic stress, illness, hormonal shifts, and emotional trauma accumulate, the body often enters a protective state. Metabolism slows. Hormonal signaling shifts. Hunger cues become unreliable. Weight gain or resistance to weight loss can occur even during periods of low intake, because energy regulation is being driven by survival physiology rather than simple calorie balance.

This is not failure. It is physiology.

The calories-in, calories-out model does not account for thyroid suppression, nervous system activation, sleep disruption, pain, trauma, or metabolic adaptation. It reduces a complex biological system to arithmetic.

Women are not machines. We are adaptive systems built for survival. Sometimes resilience looks like holding onto energy when the body does not feel safe.

The Systems That Reinforce Shame

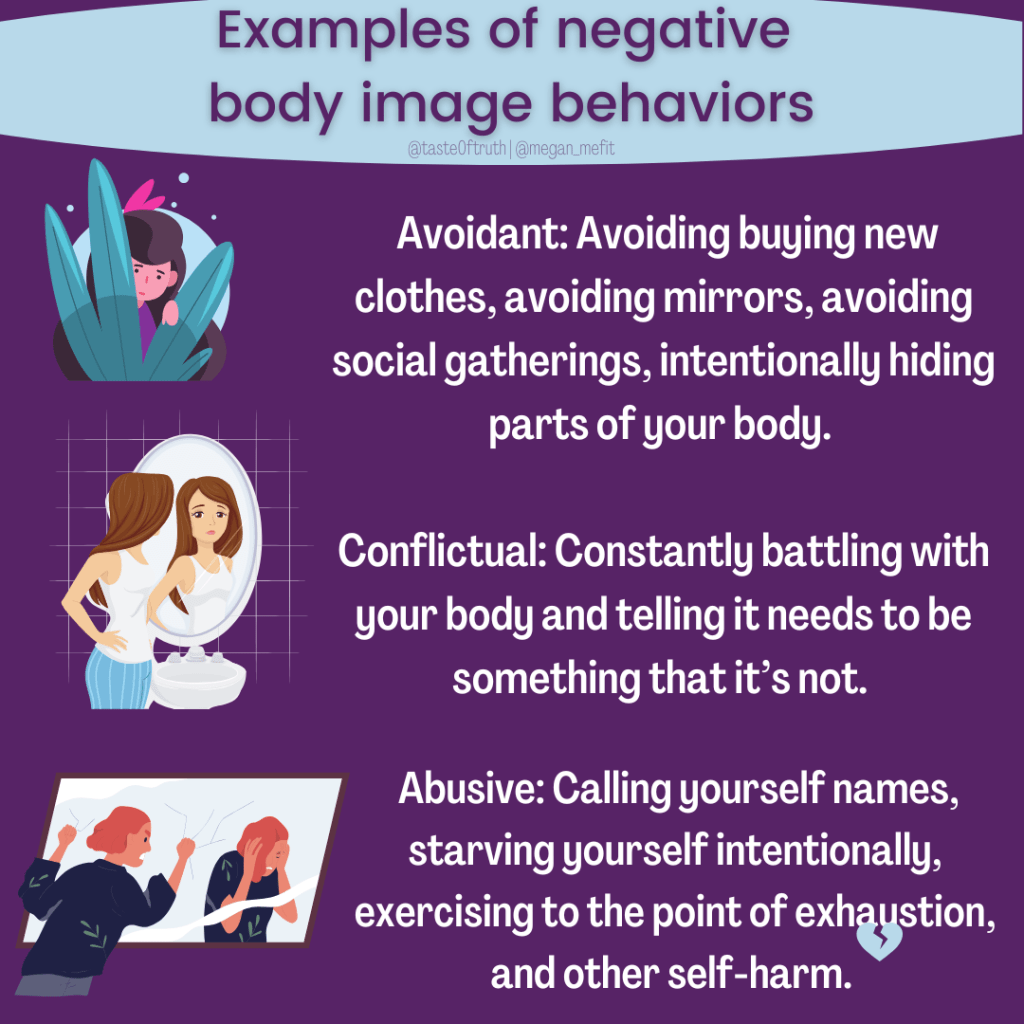

Despite this biological reality, we live in a culture that ties women’s value to discipline and appearance. When women gain weight, even under extreme circumstances, we blame ourselves before questioning the system.

Diet culture frames shrinking as virtue.

Toxic positivity encourages acceptance without context.

Industrial food environments differ radically from those our ancestors evolved in.

Medical systems often dismiss women’s pain and metabolic complexity.

Social media amplifies comparison and moralizes body size.

None of this is your fault. And all of it shapes your experience.

This is why understanding the science matters. This is why telling the truth matters. This is why sharing stories matters.

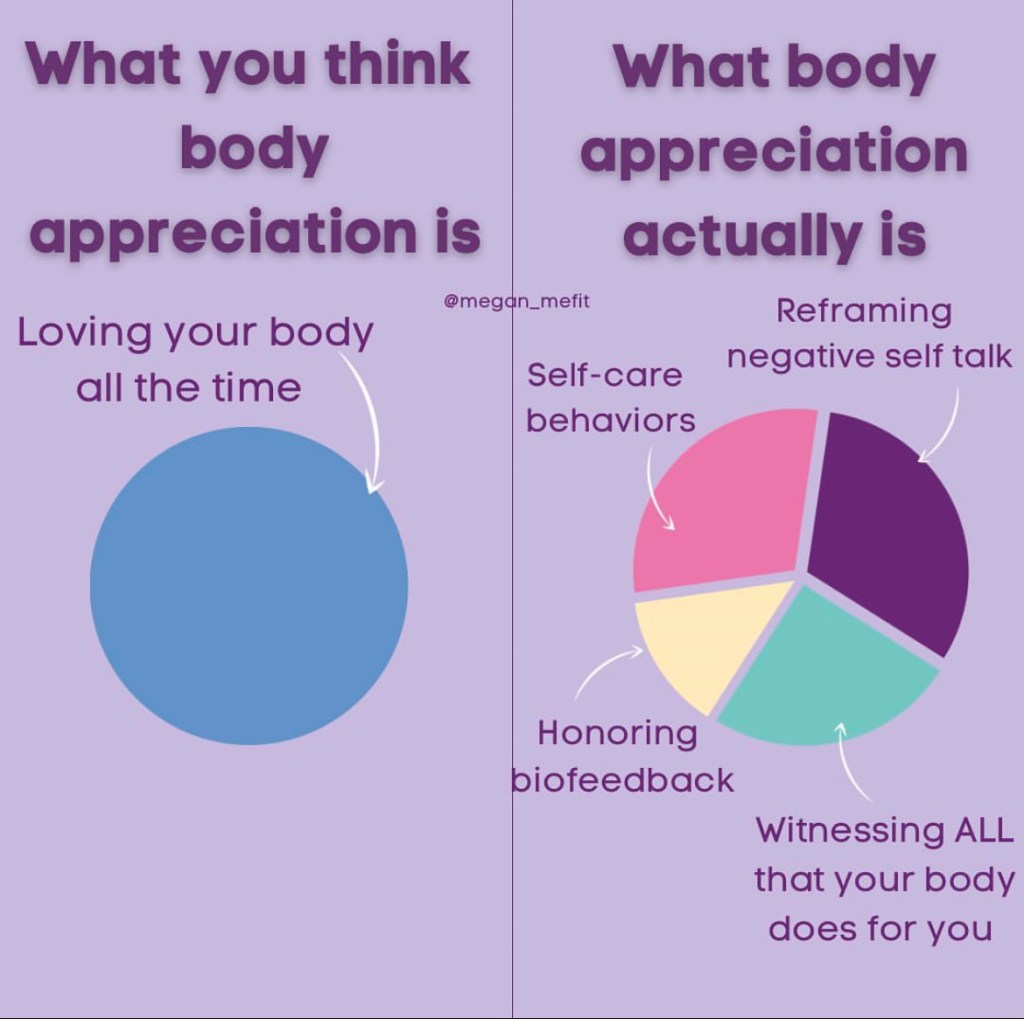

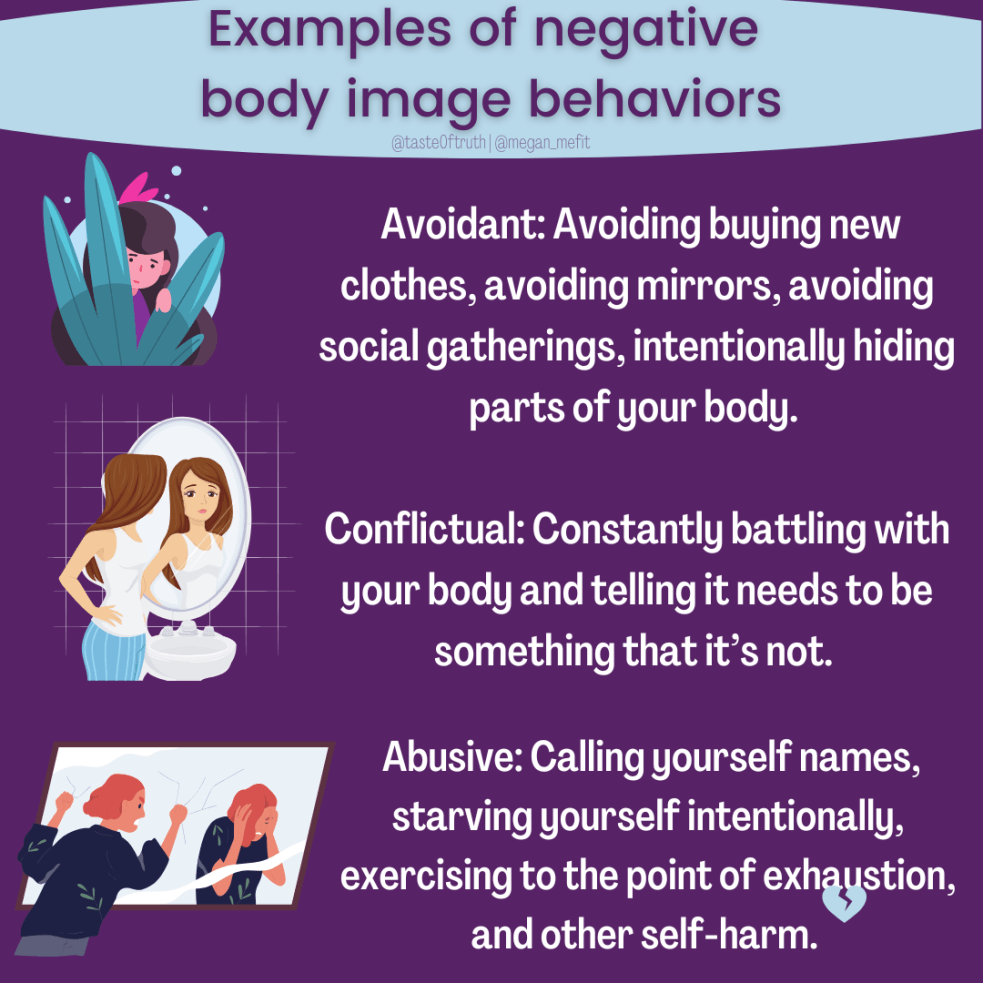

In the book, More Than a Body, Lindsay and Lexie Kite describe how women are taught to relate to themselves through constant self-monitoring. Instead of living inside our bodies, we learn to watch ourselves from the outside. We assess how we look, how we are perceived, and whether our bodies are acceptable in a given moment.

This constant self-surveillance does real harm. It pulls attention away from hunger, pain, fatigue, and intuition. It trains women to override bodily signals in favor of appearance management. And over time, it creates a split where the body is treated as a project to control rather than a system to understand or care for.

When you layer this kind of self-objectification on top of chronic stress, restriction, illness, and trauma, the result is not empowerment. It is disconnection. And disconnection makes it even harder to hear what the body needs when something is wrong.

Weight gain is not just a biological response. It becomes a moral verdict. And that is how women end up fighting bodies that are already struggling to keep them alive.

The Inheritance Ends Here

For a long time, I believed that breaking generational cycles only applied to mothers and daughters. I do not have children, so I assumed what I inherited would simply end with me, unchanged.

Brumberg’s work helped me see this differently.

What we inherit is not passed down only through parenting. It moves through tone, silence, and self-talk. It appears in how women speak about their bodies in front of others. It lives in the way shame is normalized.

I inherited a legacy of body shame. Even on the days when I still feel its weight, I am choosing not to repeat it.

For me, the inheritance ends with telling the truth about this journey and refusing to speak to my body with the same cruelty I absorbed growing up. It ends here.

Closing the Circle: Your Body Is Not Broken

I wish I could end this with a simple story of resolution. I cannot. I am still in the middle of this. I still grieve. I still struggle with eating and movement. I am still learning how to inhabit a body that feels unfamiliar.

But I know this: my body is not my enemy. She is not malfunctioning. She is adapting to a lifetime of stress, illness, restriction, and emotional weight.

If you are in a similar place, I hope this offers permission to stop fighting yourself and start understanding the patterns your body is following. Not because everything will suddenly improve, but because clarity is often the first form of compassion.

Your body is not betraying you. She is trying to keep you here.

And sometimes the most honest thing we can do is admit that we are still finding our way.

References

- Brumberg, J. J. (1997). The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls. Random House.

- Lassek, W. D., & Gaulin, S. J. C. (2011). Why Women Need Fat: How “Healthy” Food Makes Us Gain Excess Weight and the Surprising Solution to Losing It Forever. Hudson Street Press.

- Kite, L., & Kite, L. (2020). More Than a Body: Your Body Is an Instrument, Not an Ornament. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Scientific and academic sources

- Lassek, W. D., & Gaulin, S. J. C. (2006). Changes in body fat distribution in relation to parity in American women. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27(3), 173–185.

- Lassek, W. D., & Gaulin, S. J. C. (2008). Waist–hip ratio and cognitive ability. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 275(1644), 193–199.

- Dulloo, A. G., Jacquet, J., & Montani, J. P. (2015). Adaptive thermogenesis in human body-weight regulation. Obesity Reviews, 16(S1), 33–43.

- Fothergill, E., et al. (2016). Persistent metabolic adaptation after weight loss. Obesity, 24(8), 1612–1619.

- Kyle, U. G., et al. (2004). Body composition interpretation. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 79(6), 955–962.

- Simopoulos, A. P. (2016). Omega-6/omega-3 balance and obesity risk. Nutrients, 8(3), 128.

Trauma, stress, and nervous system context

- Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers. Henry Holt and Company.

- Walker, P. (2013). Complex PTSD: From Surviving to Thriving. Azure Coyote Books.