When Belief Becomes Control

This episode isn’t about religion versus religion.

It’s about power, fear, and what happens inside belief systems when conformity becomes more important than honesty.

In this conversation, I’m joined by Sigrin, founder of Universal Pagan Temple.

She’s a practicing Pagan, a witch, a public educator, and someone who speaks openly about leaving Christianity after experiencing fear-based theology, spiritual control, and shame. I want to pause here, because even as an agnostic, when I hear the word witch, my brain still flashes to the cartoon villain version. Green. Ugly. Evil. That image didn’t come from nowhere. It was taught.

One of the things we get into in this conversation is how morality actually functions in Pagan traditions, and how different that framework is from what most people assume.

She describes leaving Christianity not as rebellion, but as self-preservation. And what pushed her out wasn’t God. It was other Christians.

For many people, Christianity isn’t learned from scripture.

It’s learned from other Christians.

The judgment.

The constant monitoring.

The fear of being seen as wrong, dangerous, or spiritually compromised.

In high-control Christian environments, conformity equals safety. Questioning creates anxiety. And the fear of social punishment often becomes stronger than belief itself.

When belonging is conditional, faith turns into survival.

What We Cover in This Conversation:

Paganism Beyond Aesthetics

A lot of people hear “Paganism” and immediately picture vibes, trends, or cosplay. We spend time breaking that assumption apart.

- Sigrin explains that many beginners jump straight into ritual without actually invoking or dedicating to the divine.

- She talks about the difference between aesthetic practice and intentional practice.

- For people who don’t yet feel connected to a specific god or goddess, she offers grounded guidance on how to approach devotion without forcing it.

- We talk about the transition she experienced moving from Christianity, to atheism, to polytheism.

- We explore the role of myth, story, and symbolism in spiritual life.

- She shares her experience of feeling an energy she couldn’t deny, even after rejecting belief entirely.

- We touch on the wide range of ways Pagans relate to pantheons, including devotional, symbolic, ancestral, and experiential approaches.

The takeaway here isn’t “believe this.”

It’s that Paganism isn’t shallow, trendy, or uniform. It’s relational.

No Holy Book, No Central Authority

One of the most misunderstood aspects of Paganism is the absence of a single text or governing authority.

- Sigrin references a line she often uses: “If you get 20 witches in a room, you’ll have 40 different beliefs.”

- We talk about how Pagan traditions don’t operate under enforced doctrine or centralized belief.

- She brings up the 42 Negative Confessions from ancient Egyptian tradition as an example of ethical self-statements rather than commandments.

- These function more like reflections on character than laws imposed from above.

- We compare this to moral storytelling across different myth traditions rather than rigid rule-following.

- She emphasizes intuition and empathy as core tools for ethical decision-making.

- I add the role of self-reflection and introspection in systems without external enforcement.

This raises an important question: without a script, responsibility shifts inward.

Why This Can Be Hard After Christianity

We also talk honestly about why this freedom can be uncomfortable, especially for people leaving authoritarian religion.

- Sigrin notes how difficult it can be to release belief in hell, even after leaving Christianity.

- Fear doesn’t disappear just because belief changes.

- When morality was once externally enforced, internal trust has to be rebuilt.

- Pagan paths often require learning how to sit with uncertainty rather than replacing one authority with another.

This isn’t easier.

It’s quieter.

And it asks more of the individual.

That backdrop matters, because it shapes how Paganism gets misunderstood, misrepresented, and framed as dangerous.

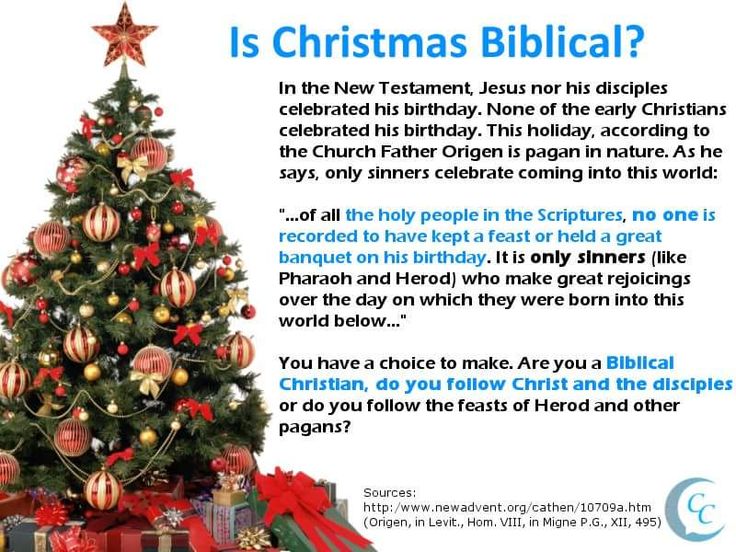

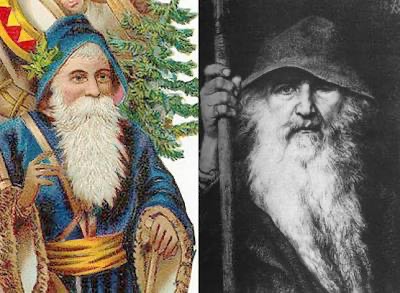

The “Pagan Threat” Narrative

One of the reasons Pagan Threat has gained attention and sparked controversy is not just its content, but whose voice it carries and how it’s framed at the outset.

- The book was written by Pastor Lucas Miles, a senior director with Turning Point USA Faith and author of other conservative religious critiques. The project is positioned as a warning about what Miles sees as threats to the church and American society. The foreword was written by Charlie Kirk, founder of Turning Point USA. His introduction positions the book as urgent for Christians to read.

From there, the book makes a striking claim:

- It describes Christianity as a religion of freedom, while framing Paganism as operating under a hive mind or collective groupthink.

A key problem is which Paganism the book is actually engaging.

- The examples Miles focuses on overwhelmingly reflect liberal, online, or activist-adjacent Pagan spaces, particularly those aligned with progressive identity politics.

- That narrow focus gets treated as representative of Paganism as a whole.

- Conservative Pagans, reconstructionist traditions, land-based practices, and sovereignty-focused communities are largely ignored.

As a result, “wokeness” becomes a kind of explanatory shortcut.

- Modern political anxieties get mapped onto Paganism.

- Gender ideology, progressive activism, and left-leaning culture get blamed on an ancient and diverse spiritual category.

- Paganism becomes a convenient container for everything the author already opposes.

We also talk openly about political realignment, and why neither of us fits cleanly into the right/left binary anymore. I raise the importance of actually understanding Queer Theory, rather than using “queer” as a vague identity umbrella.

To help visualize this, I reference a chart breaking down five tiers of the far left, which I’ll include here for listeners who want context.

Next, in our conversation, Sigrin explains why the groupthink accusation feels completely inverted to anyone who has actually practiced Paganism.

- Pagan traditions lack central authority, universal doctrine, or an enforcement mechanism.

- Diversity of belief isn’t a flaw. It’s a defining feature.

- Pagan communities often openly disagree, practice differently, and resist uniformity by design.

The “hive mind” label ignores that reality and instead relies on a caricature built from a narrow and selective sample.

“Trotter and Le Bon concluded that the group mind does not think in the restricted sense of the word. In place of thoughts, it has impulses, habits, and emotions. Lacking an independent mind, its first impulse is usually to follow the example of a trusted leader. This is one of the most firmly established principles of mass psychology.” Propaganda by Edward L. Bernays

We contrast this with Christian systems that rely on shared creeds, orthodoxy, and social enforcement to maintain cohesion.

Accusations of groupthink, in that context, often function as projection from environments where conformity is tied to spiritual safety.

In those systems, agreement is often equated with faithfulness and deviation with danger.

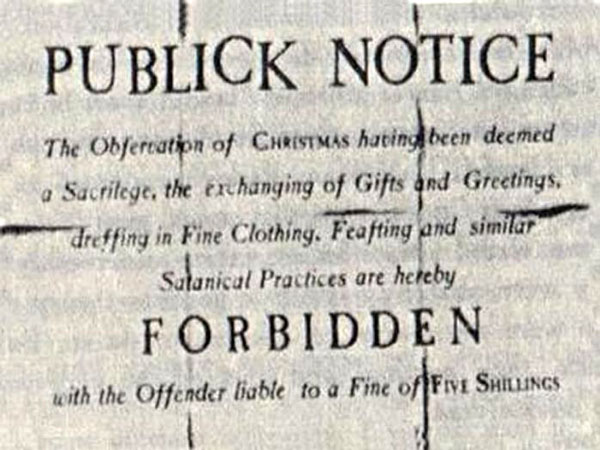

Globalism, Centralization, and Historical Irony

We end the conversation by stepping back and looking at the bigger historical picture.

- The book positions Christianity as the antidote to globalism.

- At the same time, it advocates coordinated religious unification, political mobilization, and cultural enforcement.

- That contradiction becomes hard to ignore once you zoom out historically.

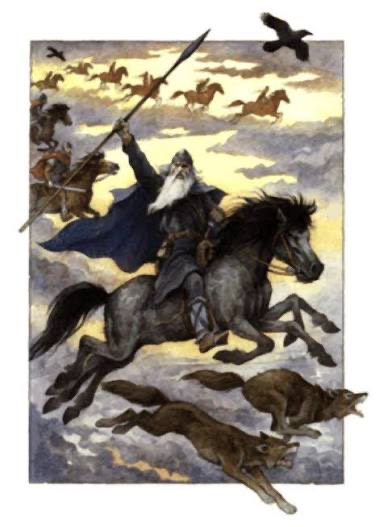

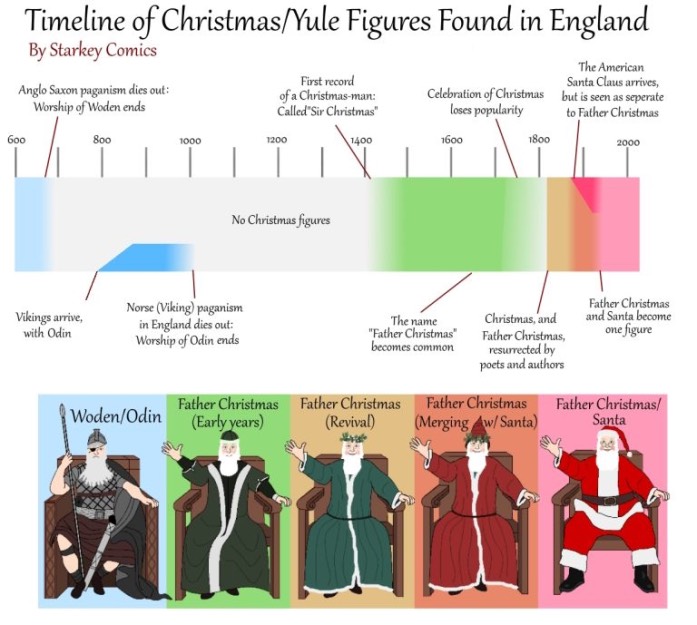

Sigrin points out that pre-Christian Pagan worlds were not monolithic.

- Ancient polytheist societies were highly localized.

- City-states and regions had their own gods, rituals, myths, and customs.

- Religious life varied widely from place to place, even within the same broader culture.

I reference The Darkening Age by Catherine Nixey, which documents this diversity in detail.

- Pagan societies weren’t unified under a single doctrine.

- There was no universal creed to enforce across regions.

- Difference wasn’t a problem to be solved. It was normal.

Christianity, by contrast, became one of the first truly globalizing religious systems.

- A single truth claim.

- A centralized authority structure.

- A mandate to replace local traditions rather than coexist with them.

That history makes the book’s framing ironic.

- Paganism gets labeled “globalist,” despite being inherently local and decentralized.

- Christianity gets framed as anti-globalist, while proposing further consolidation of belief, power, and authority.

What This Is Actually About

This isn’t about attacking Christians as people.

And it’s not about defending Paganism as a brand.

It is a critique of how certain forms of Christianity function when belief hardens into certainty and certainty turns into control.

Fear-based religion and fear-based ideology share the same problem.

They promise safety.

They demand conformity.

And they struggle with humility.

That doesn’t describe every Christian.

But it does describe systems that rely on fear, surveillance, and moral enforcement to survive.

What I appreciate about this conversation is the reminder that spirituality doesn’t have to look like domination, hierarchy, or a battle plan.

It can be rooted. Local. Embodied.

It can ask something of you without erasing you.

And whether someone lands in Paganism, Christianity, or somewhere else entirely, the question isn’t “Which side are you on?”

It’s whether your beliefs make you more honest, more grounded, and more responsible for how you live.

That’s what I hope people sit with after listening.

Ways to Support Universal Pagan Temple

Every bit of support helps keep the temple lights on, create more free content, and maintain our community altar. Thank you from the bottom of my heart!

Buy me a coffee (one-time support)

https://www.buymeacoffee.com/UniversalPaganTemple

Make a direct donation to the temple

https://www.paypal.com/donate?hosted_button_id=6TMJ4KYHXB36U

Become a Patreon/Subscribestar member (monthly perks & exclusive content)

https://www.patreon.com/universalpagantemple

https://www.subscribestar.com/the-pagan-prepper

Join our Substack community (articles, rituals & updates)

https://universalpagantemple.substack.com

Book a Rune or Tarot reading (Etsy)

https://www.etsy.com/shop/RunicGifts

Grab our books on Amazon

•Wicca & Magick: Complete Beginner’s Guide

https://www.amazon.com/Wicca-Magick-Complete-Beginners-Guide-ebook/dp/B019MZN8LQ

* Runes: Healing and Diet by Sigrún and Freya Aswynn

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B08FP25KH4#averageCustomerReviewsAnchor

• The Egyptian Gods and Goddesses for Beginners

https://www.amazon.com/Egyptian-Gods-Goddesses-Beginners-Worshiping/dp/1537100092

Even just watching, liking, commenting, and sharing is a huge help!

Blessed be