Welcome to Taste Test Thursday! You know how online debates often turn into full-blown keyboard wars? People lash out with rage when their beliefs whether political, religious, or social are challenged. But why? What’s behind these intense, emotional responses?

What if it’s not just about bad ideas, but something deeper a brain imbalance? What if our need for certainty and addiction to outrage comes from the way our brains are wired to process the world?

Today we’re diving into the neuroscience behind these defensive reactions. We’ll see how the brain’s wiring for survival influences everything from ideological rigidity to emotional hijacking. We’re setting the stage for something important that we’ll explore this upcoming Tuesday how Complex PTSD and PTSD are NOT the same thing. This is an episode you won’t want to miss, especially if you’ve ever felt stuck in a cycle of intense emotional reactions that you just can’t control.

Let’s review something we’ve discussed before: Amygdala Hijacking. If you remember, the amygdala is a part of our brain that processes emotions like fear and anger. Now, when the amygdala gets triggered especially in stressful or traumatic situations it can completely bypass the more rational prefrontal cortex. This results in what we call an “emotional hijack,” where the brain goes straight into fight-or-flight mode often in situations that don’t actually require that level of reaction.

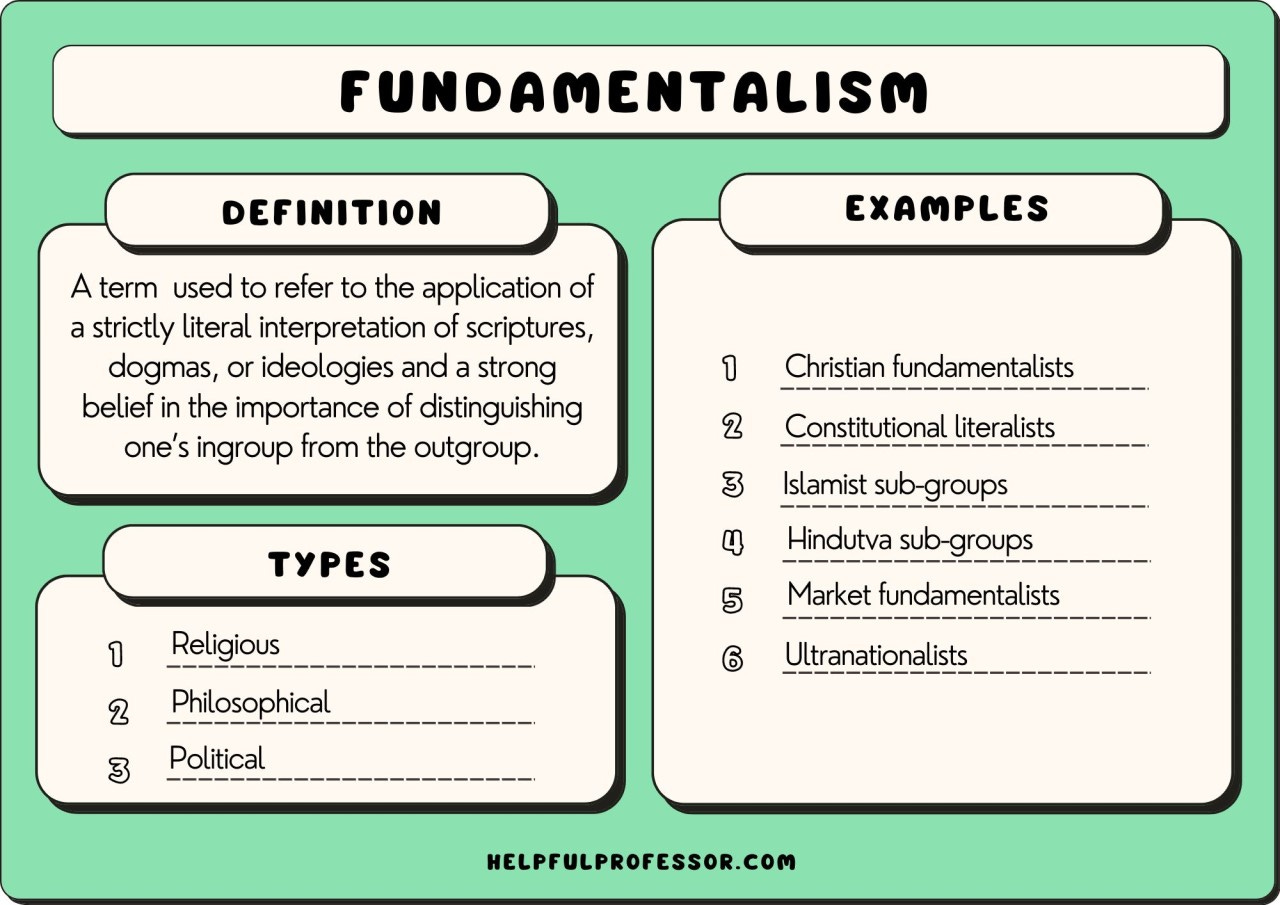

This kind of response helps explain why some people find comfort in fundamentalism.

“At its most basic, the allure of fundamentalism, whether religious or ideological, liberal or conservative, is that it provides an appealing order to things that are actually disorderly.”

— Peter Mountford The Dismal Science

That line hits at something crucial we have explored many times before: the human brain craves order, especially in the face of chaos. The illusion of control is one of our brain’s favorite coping mechanisms and when we find a system (religious, political, or otherwise) that delivers black-and-white certainty? You get a dopamine hit.

Rigid ideologies offer a tidy framework that feels safe and predictable especially in times of confusion, disillusionment, or personal crisis. That’s not just philosophy. That’s neurology.

When Chaos Was the Norm, Control Becomes a Coping Mechanism

For many of us, rigid beliefs aren’t just intellectual frameworks. They’re emotional survival strategies.

The need for control, the drive for perfection, the desire to be “good enough” to earn love these weren’t just quirks of personality. They were adaptations to childhoods where emotional needs weren’t met. And like many people who grew up in households marked by emotional neglect, those patterns shaped everything: our relationships, our careers, our bodies, and the ideologies we clung to.

Psychologists like Alice Miller and Elan Golomb have long noted how children raised in emotionally unavailable or narcissistic homes often create a false self a version of themselves designed to gain approval and avoid rejection.

It’s a blueprint that gets carried into adulthood, often unconsciously.

That’s why fundamentalist spaces feel so magnetic to people with childhood trauma. They offer:

- Clear rules instead of emotional chaos

- “Unconditional” love that’s actually highly conditional

- A surrogate parent in the form of a deity or ideology that tells you who to be

Religious trauma often echoes family trauma—because it’s a new version of the same wound.

When Identity Is Built on Compliance

When a belief system rewards obedience over curiosity, it recreates the dynamics of an authoritarian household. You’re loved when you perform correctly. You belong when you don’t question. You’re “good” when you conform.

So what happens when you start to deconstruct?

The moment someone questions the “truth,” it’s perceived as a betrayal—not just of doctrine, but of identity and tribe. And that’s when we see:

- Verbal attacks – Heretic. Traitor. Bigot.

- Social ostracism – Canceled. Shunned. Ghosted.

- Online harassment – Dogpiling and moral outrage.

- Even physical aggression – History is full of examples, from witch hunts to ideological purges.

But this isn’t just about “bad actors.” It’s about brains shaped by fear.

When your childhood taught you that being wrong = being unloved, then someone challenging your beliefs doesn’t just feel uncomfortable it feels unsafe.

Disagreement triggers:

- Cognitive dissonance – That gut-wrenching anxiety when facts don’t fit your worldview

- Fear of consequences – Hellfire or public shaming

- Loss of self – Because the belief was the identity

- Loss of community – The people who “loved” you might now condemn you

The Brain’s Role in Certainty Addiction

Neuroscience adds another layer here—one that makes ideological rigidity more understandable, even if it’s not excusable.

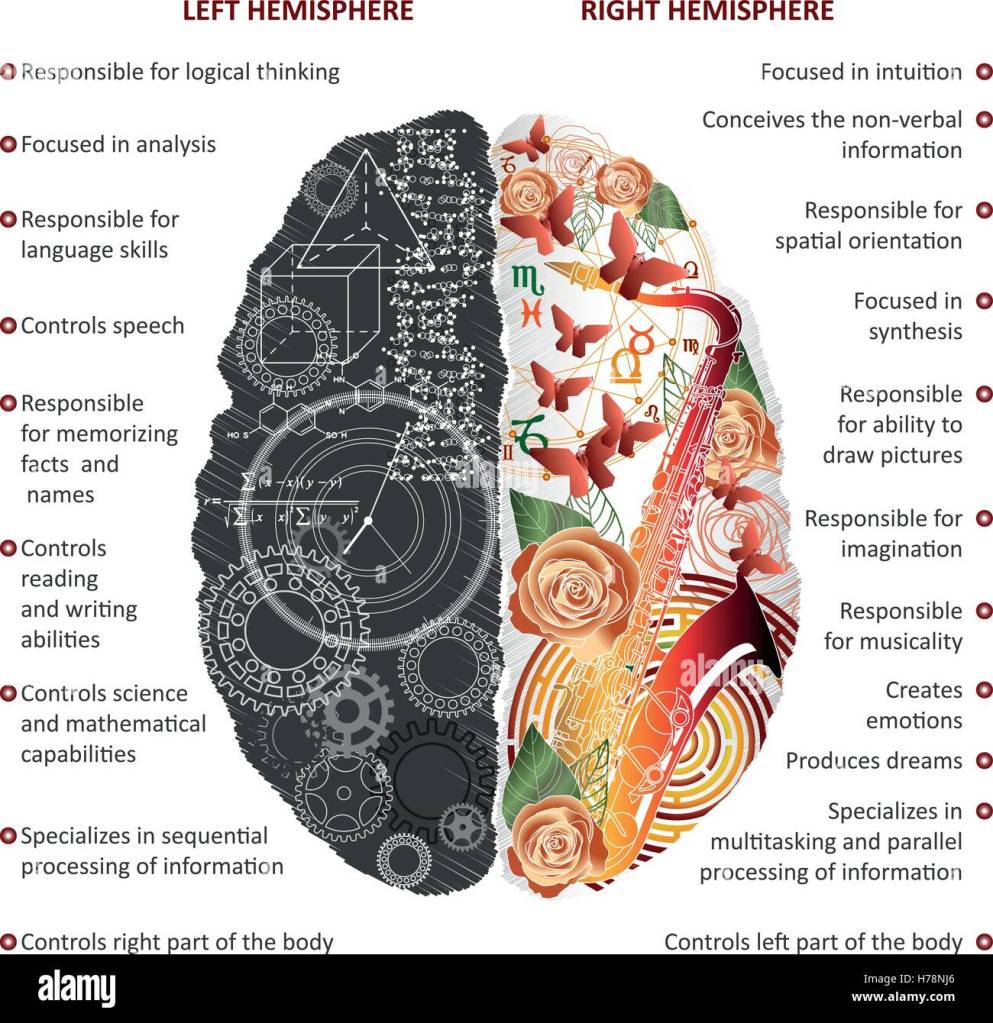

Dr. Iain McGilchrist, in The Master and His Emissary, outlines how the brain’s left and right hemispheres don’t just process information differently—they perceive reality differently.

❌ Not: “Left brain = logic, Right brain = creativity.”

✅ But: “Left brain = control, categorization, and certainty. Right brain = context, relationship, and meaning.”

In a balanced brain, the right hemisphere leads—it sees the big picture, embraces nuance, and stays grounded in lived reality. The left hemisphere refines, classifies, and helps us act.

But modern culture has flipped the script. We’ve let the left hemisphere hijack our perception, reducing the complex to the manageable, the mysterious to the measurable. In this flipped hierarchy:

- Ambiguity feels threatening

- Context gets stripped away

- Relationship is sacrificed for abstraction

- And certainty becomes a kind of drug

That’s why ideological possession feels so safe. The left brain loves a clear system, even if it’s oppressive. It would rather be certain and wrong than uncertain and real.

So, when someone questions your belief, it’s not just inconvenient. It shatters the left brain’s illusion of control. And when that illusion is all, you’ve known since childhood, the reaction isn’t just intellectual-it’s existential. a threat.

When Belief Becomes Identity

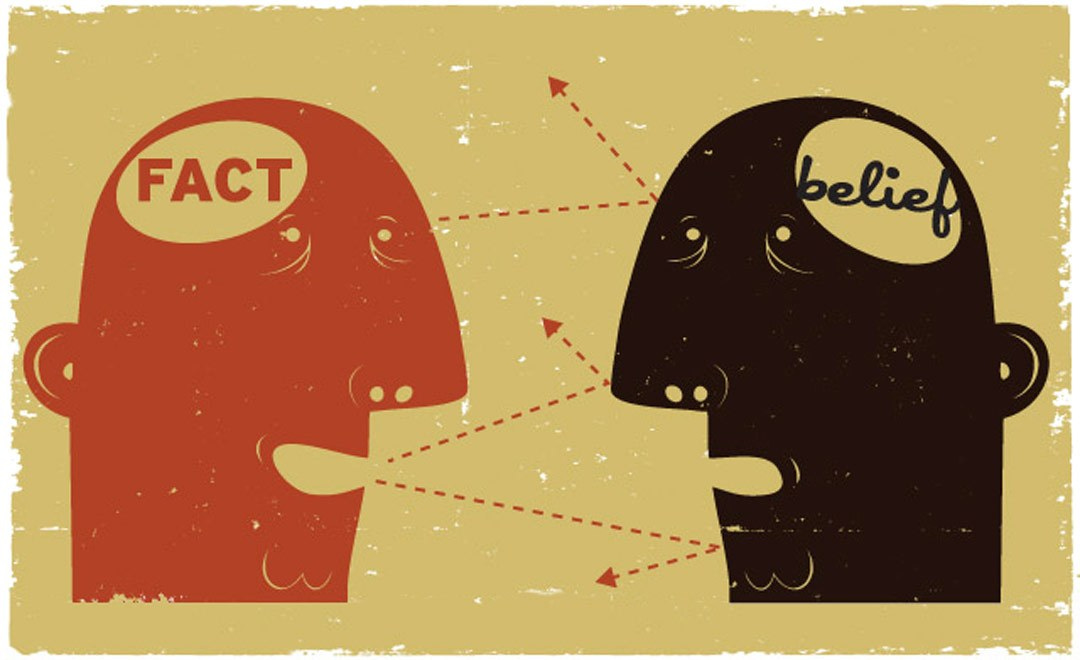

Jonathan Haidt, in The Righteous Mind, explains that we don’t arrive at beliefs through pure logic. We have moral intuitions quick, gut-level judgments and then our reasoning brain (usually the left hemisphere) steps in, not to find the truth, but to defend the tribe.

The moment someone questions our “truth,” we don’t hear it as a conversation—we hear it as an attack.

What happens next?

Verbal Attacks:

When someone questions a core belief, the response often isn’t curiosity—it’s insults, belittling, or outright contempt. In faith spaces, that might look like calling someone a heretic. In political spaces, it’s labels like traitor, bigot, or grifter.

Social Ostracism:

Both religious and political groups punish deviation. Doubters are canceled, excommunicated, or ghosted. Deconstruct your faith? You might lose your church community. Question political orthodoxy? You might lose friends—or your job.

Online Harassment:

The algorithm rewards outrage. Post a thoughtful question about a sacred ideology and you’ll get dogpiled. Our moral tastebuds, as Haidt would say, are being hijacked by dopamine-fueled tribalism.

Physical Aggression:

At the extremes, ideological certainty becomes dangerous. From holy wars to revolutions, the ugliest parts of history stem from one belief: we’re right, and they’re evil.

Why We React This Way: The Psychology of Threat

When beliefs are fused with identity, disagreement feels like annihilation. Especially when the community around us reinforces that fusion. Here’s the pattern:

- Fear of Deviation: Questioning is framed as betrayal either spiritual or social.

- Cognitive Dissonance: New ideas create discomfort, and doubling down feels safer than rethinking.

- Fear of Consequences: From hellfire to being canceled, the cost of questioning is high.

- Identity Threat: When belief equals self-worth, letting go feels like losing yourself.

- Social Pressure: Communities often reward conformity and punish dissent.

This is where McGilchrist and Haidt align beautifully: one shows how the brain gets hijacked by the need for control, the other shows how morality binds us to our tribe and blinds us to complexity.

Make-Believe, Morality, and the Group

In our episode with Neil Van Leeuwen, author of Religion as Make-Believe, we unpacked another crucial insight: factual beliefs are flexible, but identity-based beliefs aren’t. They don’t require evidence. In fact, falsehoods often serve the group better because they signal loyalty, not logic.

This is why both sides of a political aisle can believe obviously contradictory things because the truth is secondary to belonging. And once we belong, we don’t think critically–we defend instinctively.

The Antidote: Intellectual Humility

The only way out is through a kind of self-aware disruption.

- Open Dialogue: Spaces where disagreement isn’t punished—but explored.

- Supportive Community: Groups that allow for doubt, evolution, and honest questioning.

- Personal Reflection: A willingness to examine the stories we tell ourselves—and why we need them.

- Interdisciplinary Curiosity: Instead of staying in one thought silo, we pull from neuroscience, sociology, philosophy, and lived experience.

Fundamentalism, at its core, is the elevation of certainty over curiosity. But healing, freedom, and truth? They live on the other side of that certainty.

So, what’s one belief you once clung to tightly only to realize it wasn’t the whole truth?

Let’s talk about it in the comments.

And remember:

Maintain your curiosity, embrace skepticism, and keep tuning in. 🎙️🔒

We’re not here to worship reason or reject it.

We’re here to see more clearly.Sources:

- Dr. Iain McGilchrist – Left and Right Hemisphere Functions

McGilchrist, Iain. The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World. Yale University Press, 2009.- Alice Miller – Emotional Neglect and the False Self

Miller, Alice. The Drama of the Gifted Child: The Search for the True Self. Basic Books, 1997.- Elan Golomb – Narcissistic Parenting and Emotional Consequences

Golomb, Elan. Trapped in the Mirror: Adult Children of Narcissists in Their Struggle for Self. William Morrow, 1992.

- Neil Van Leeuwen – Religious Trauma and Belief Systems

Van Leeuwen, Neil. Religion as Make-Believe: The Religious Imagination and the Design of the World. Cambridge University Press, 2021.- Jonathan Haidt – Moral Psychology and Group Loyalty

Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion. Pantheon Books, 2012.