When Willpower Isn’t Enough: Media, Metabolism, and the Myth of Transformation

You’re listening to Taste Test Thursdays–a space for the deep dives, the passion projects, and the stories that didn’t quite fit the main course. Today, we’re hitting pause on the intense spiritual and political conversations we usually have to focus on something just as powerful: how technology shapes our bodies, minds, and behaviors. We’ll be unpacking a recent Netflix documentary that highlights research and concepts we’ve explored before, shining a light on the subtle ways screens and media program us and why it matters more than ever.

I have a confession: I watched The Biggest Loser. Yep. Cringe, right? Back in 2008, when I was just starting to seriously focus on personal training (I got my first certification in 2006 but really leaned in around 2008), this show was everywhere. It was intense, dramatic, and promised transformation—a visual fairy tale of sweat, willpower, and discipline.

Looking back now, it’s so painfully cringe, but I wasn’t alone. Millions of people were glued to the screens, absorbing what the show told us about health, fat loss, and success. And the new Netflix documentary Fit for TV doesn’t hold back. It exposes the extreme, sometimes illegal methods used to push contestants: caffeine pills given by Jillian Michaels, emotional manipulation, extreme exercise protocols, and food as a weapon. Watching it now, I can see how this programming shaped not just contestants, but an entire generation of viewers—including me.

Screens Aren’t Just Entertainment

Laura Dodsworth nails it in Free Your Mind:

“Television is relaxing, but it also is a source of direct and indirect propaganda. It shapes your perception of reality. What’s more, you’re more likely to be ‘programmed’ by the programming when you are relaxed.”

This is key. Television isn’t just a casual distraction. It teaches, it socializes, and it normalizes behavior. A study by Lowery & DeFleur (Milestones in Mass Communication Research, 1988) called TV a “major source of observational learning.” Millions of people aren’t just entertained—they’re learning what’s normal, acceptable, and desirable.

Dodsworth also warns:

“Screens do not show the world; they obscure. The television screen erects visual screens in our mind and constructs a fake reality that obscures the truth.”

And that’s exactly what reality diet shows did. They created a distorted narrative: extreme restriction and punishment equals success. If you just try harder, work longer, and push further, your body will cooperate. Except, biology doesn’t work like that.

The Metabolic Reality

Let’s dig into the science. The Netflix documentary Fit for TV references the infamous Biggest Loser study, which tracked contestants years after the show ended. Here’s what happened:

- Contestants followed extreme protocols: ~1,200 calories a day, 90–120 minutes of intense daily exercise (sometimes up to 5–8 hours), and “Franken-foods” like fat-free cheese or energy drinks.

- They lost massive amounts of weight on TV. Dramatic, visible transformations. Ratings gold.

- Six years later, researchers checked back: most regained ~70% of the weight. But the real kicker? Their resting metabolic rate (RMR) was still burning 700 fewer calories per day than baseline—500 calories less than expected based on regained body weight.

- In everyday terms? Imagine you used to burn 2,000 calories a day just by living. After extreme dieting, your body was burning only 1,300–1,500 calories a day, even though you weighed almost the same. That’s like your body suddenly deciding it needs to hold on to every calorie, making it much harder to lose weight—or even maintain it—no matter how “good” you eat or how much you exercise.

This is huge. It shows extreme dieting doesn’t just fail long-term; it fundamentally rewires your metabolism.

Why?

- Leptin crash: The hormone that tells your brain you’re full plummeted during the show. After weight regain, leptin rebounded, but RMR didn’t. Normally, these rise and fall together—but the link was broken.

- Loss of lean mass: Contestants lost ~25 pounds of muscle. Regaining some of it didn’t restore metabolic function.

- Hormonal havoc: Chronic calorie deficits and overtraining disrupted thyroid, reproductive, and adrenal hormones. Weight loss resistance, missed periods, hair loss, and constant cold are all part of the aftermath.

Put bluntly: your body is not passive. Extreme dieting triggers survival mode, conserving energy, increasing hunger, and slowing metabolism.

Read more:

Personal Lessons: Living It

I know this from my own experience. Between May 2017 and October 2018, I competed in four bodybuilding competitions. I didn’t prioritize recovery or hormone balance, and I pushed my body way too hard. The metabolic consequences? Echoes of the Biggest Loser study:

- Slowed metabolism after prep phases.

- Hormonal swings that made maintaining progress harder.

- Mental fatigue and burnout from extreme restriction and exercise.

Diet culture and TV had me convinced that suffering = transformation. But biology doesn’t care about your willpower. Extreme restriction is coercion, not empowerment.

Read more:

From Digital Screens to Unrealistic Bodies

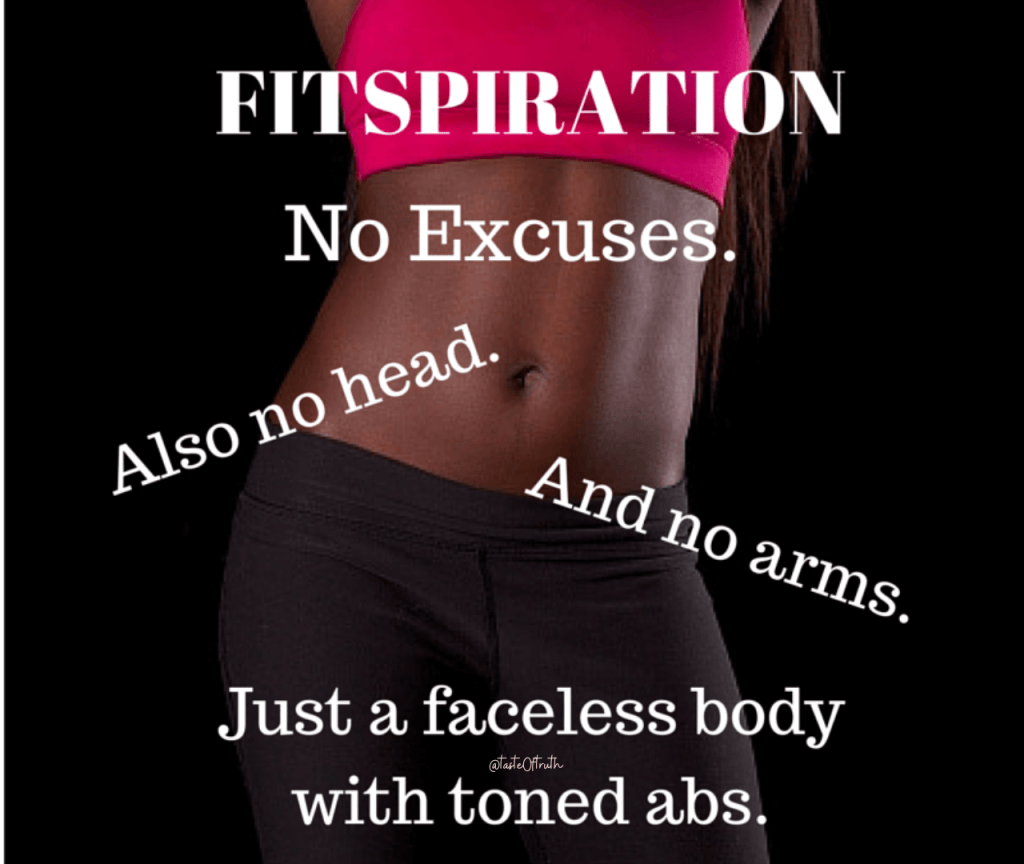

This isn’t just a TV problem. The same mechanisms appear in social media fitness culture, or “fitspiration.” In a previous podcast and blog, From Diary Entries to Digital Screens: How Beauty Ideals and Sexualization Have Transformed Over Time, we discussed the dangerous myth: hard work guarantees results.

Fitness influencers, trainers, and the “no excuses” culture sell the illusion that discipline alone equals success. Consistency and proper nutrition matter—but genetics set the foundation. Ignoring this truth fuels:

- Unrealistic expectations: People blame themselves when they don’t achieve Instagram-worthy physiques.

- Overtraining & injury: Chasing impossible ideals leads to chronic injuries and burnout.

- Disordered eating & supplement abuse: Extreme diets, excessive protein, or PEDs are often used to push past natural limits.

The industry keeps genetics under wraps because the truth doesn’t sell. Expensive programs, supplement stacks, and influencer promises rely on people believing they can “buy” someone else’s results. Many extreme physiques are genetically gifted and often enhanced, yet presented as sheer willpower. The result? A culture of self-blame and impossible standards.

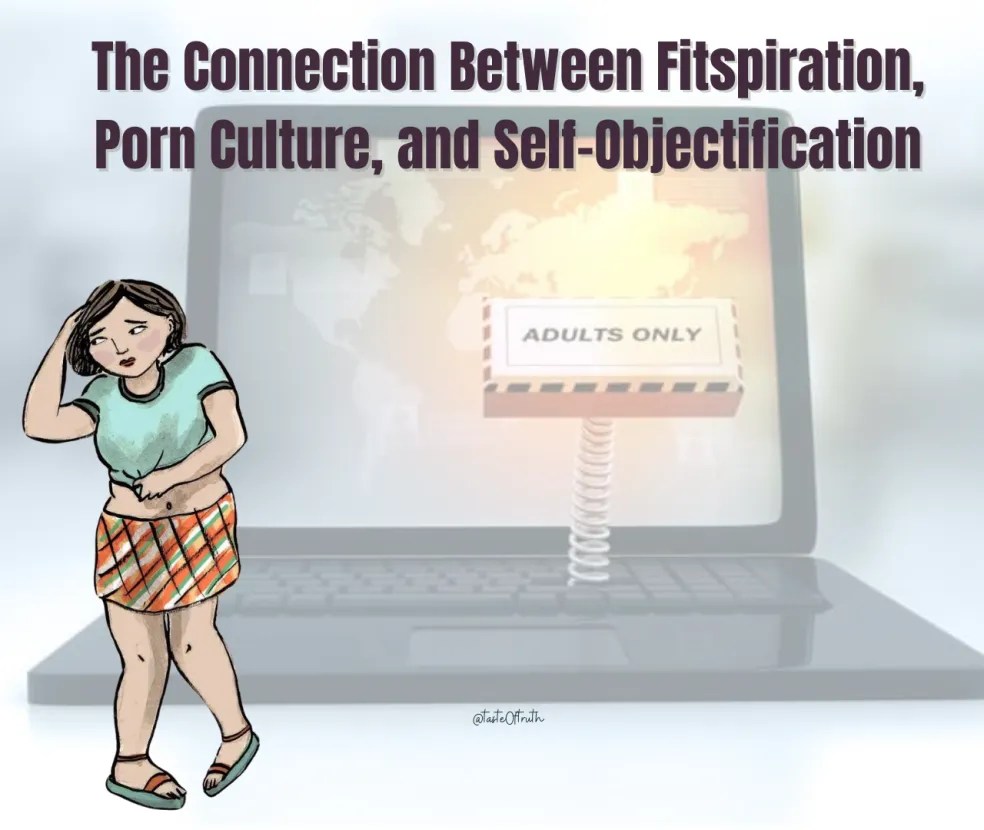

Fitspiration and Self-Objectification

The 2023 study in Computers in Human Behavior found that exposure to fitspiration content increases body dissatisfaction, especially among women who already struggle with self-image. Fitspo encourages the internalized gaze that John Berger described in Ways of Seeing:

“A woman must continually watch herself. She is almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself… she comes to consider the surveyor and the surveyed within her as the two constituent yet always distinct elements of her identity as a woman.”

One part of a woman is constantly judging her body; the other exists as a reflection of an ideal. Fitness becomes performative, not functional. Anxiety, depression, disordered eating, and self-objectification follow. Fitness culture no longer focuses on strength or health—it’s about performing an idealized body for an audience.

The Dangerous Pipeline: Fitspo to Porn Culture

This extends further. Fitspiration primes women to see themselves as objects, which feeds directly into broader sexualization. Porn culture and the sex industry reinforce the same dynamic: self-worth tied to appearance, desire, and external validation. Consider these stats:

- Over 134,000 porn site visits per minute globally.

- 88% of porn scenes contain physical aggression, 49% verbal aggression, with women overwhelmingly targeted (Bridges et al., 2010).

- Most youth are exposed to pornography between ages 11–13 (Wright et al., 2021).

- 91.5% of men and 60.2% of women report watching porn monthly (Solano, Eaton, & O’Leary, 2020).

Fitspiration teaches the same objectification: value is appearance-dependent. Social media and reality TV prime us to obsess over performance and image, extending beyond fitness into sexualization and body commodification.

Read more:

Netflix Documentary: The Dark Side

Fit for TV exposes just how far the show went:

- Contestants were given illegal caffeine pills to keep energy up.

- Trainers manipulated emotions for drama—heightened stress, shame, and competitiveness.

- Food was weaponized—rationed, withheld, or turned into rewards/punishments.

- Exercise protocols weren’t just intense—they were unsafe, designed to produce dramatic visuals for the camera.

The documentary also makes it clear: these methods weren’t isolated incidents. They were systemic, part of a machine that broadcasts propaganda as entertainment.

The Bigger Picture: Propaganda, Screens, and Social Conditioning

Dodsworth again:

“Watching TV encourages normative behavior.”

Shows like The Biggest Loser don’t just affect contestants—they socialize an audience. Millions of viewers internalize: “Success = willpower + suffering + restriction.” Social media amplifies this further, nudging us constantly toward behaviors dictated by advertisers, algorithms, and curated narratives.

George Orwell imagined a world of compulsory screens in 1984. We aren’t there yet—but screens still shape behavior, expectations, and self-perception.

The good news? Unlike Orwell’s telescreens, we can turn off our TVs. We can watch critically. We can question the values being sold to us. Dodsworth reminds us:

“Fortunately for us, we can turn off our television and we should.”

Breaking Free

Here’s the takeaway for me—and for anyone navigating diet culture and fitness media:

- Watch critically: Ask, “What is this really teaching me?”

- Respect biology: Your body fights extreme restriction—it’s not lazy or weak.

- Pause before you absorb: Screens are powerful teachers, but you have the final say.

The bigger question isn’t just “What should I eat?” or “How should I train?” It’s:

Who’s controlling the story my mind is telling me, and who benefits from it?

Reality shows like The Biggest Loser and even social media feeds are not neutral. They are propaganda machines—wrapped in entertainment, designed to manipulate perception, reward suffering, and sell ideals that are biologically unsafe.

I’ve lived some of those lessons firsthand. The scars aren’t just physical—they’re mental, hormonal, and metabolic. But the first step to freedom is seeing the screen for what it really is, turning it off, and reclaiming control over your body, mind, and reality.

Thank you for taking the time to read/listen!

🙏 Please help this podcast reach a larger audience in hope to edify & encourage others! To do so: leave a 5⭐️ review and send it to a friend! Thank you for listening! I’d love to hear from you, find me on Instagram! @taste0ftruth , @megan_mefit , Pinterest! Substack and on X!

Until then, maintain your curiosity, embrace skepticism, and keep tuning in! 🎙️🔒

🆕🆕This collection includes books that have deeply influenced my thinking, challenged my assumptions, and shaped my content. Book Recommendations – Taste0ftruth Tuesdays