How Suppression Shapes Our Bodies, Minds, and the World We Live In

Hey hey, Welcome back! Today’s episode connects beautifully to something many of you resonated with in my earlier show, Science or Stagnation? The Risk of Unquestioned Paradigms. In that episode, we talked about scientism… not science itself, but the dogma that forms around certain scientific ideas.

That’s why voices like Rupert Sheldrake have always fascinated me. Sheldrake, for those unfamiliar, isn’t a fringe crank. He’s a Cambridge-trained biologist who dared to question what he calls the “ten dogmas of modern science”: that nature is mechanical, that the mind is only the brain, that the laws of nature are fixed, that free will is an illusion, and so on.

When he presented these questions in a TED Talk, it struck such a nerve that the talk was quietly taken down. And that raised an obvious question: If the ideas are so wrong… why not let them stand and fall on their own? Why censor them unless they hit something tender? All of this sets the stage for today’s conversation.

Because the theory we’re exploring, Social Miasm Theory, fits right inside that tension between mainstream assumptions and the alternative frameworks we often dismiss too quickly.

My friend Stephinity Salazar just published a fascinating piece of research arguing that suppression (of toxins, trauma, emotion, and truth) is the root pattern underlying both chronic illness and our wider social dysfunction. It’s a theory that steps outside the materialist worldview and challenges the mechanistic lens we’ve all been taught to see through.

You don’t have to agree with everything…that’s not the goal here.

What I love is the chance to explore, to ask good questions, and to stay grounded while examining ideas that stretch our understanding.

This blog is your guide to the episode, so you can track the concepts, explore the references, and dive deeper while you listen.

So, with that, let’s dive into Social Miasm Theory: what it is, where it comes from, why it matters, and what it might reveal about the world we’re living in today.

What Are Miasms, Anyway?

To anchor our conversation, Stephinity starts by grounding the concept of “miasms” in its homeopathic roots. Historically, Samuel Hahnemann (founder of homeopathy) described three primary miasms:

- Psora, linked to scabies or skin conditions

- Syphilis, associated with destructive disease

- Sycosis, with overgrowth and tissue proliferation

Since then, the theory has expanded. Many modern homeopaths now talk about five chronic miasms, adding:

- Tubercular (linked to tuberculosis, respiratory issues) Homeopathy 360

- Cancer miasm, considered a complex blend of the other miasms. homeopathyforwomen.org

These aren’t diseases…they’re patterns. A kind of “constitutional operating system.”

Stephinity’s work takes this a step further:

If individuals can have miasms, societies can too.

It’s an ambitious idea. And honestly? A compelling one when you consider what’s happening globally.

Why Social Miasm Theory Matters

Suppression doesn’t stay in the body. It echoes outward into culture, politics, ecosystems, and collective behavior.

She breaks suppression into four types:

- Toxic suppression: chemicals, pollutants, EMFs, pathogens

- Emotional suppression: trauma, grief, stress, unprocessed feelings

- Psychological suppression: denial, cognitive dissonance, fear-driven attachment to ideology

- Truth suppression: propaganda, censorship, disinformation, scientific dogma

When these forms of suppression accumulate, she argues, they create a “social miasm”: a pathological field that shapes everything from public health to political polarization.

Even if you don’t buy every mechanism she proposes, the metaphor works. And the patterns are hard to ignore.

Evidence, Epistemology, and Skeptics: What Counts as “Real”?

This is the part my skeptical listeners will perk up for.

In the interview, I asked her the question I knew many of you were thinking:

“How do you define evidence within this framework? What would you want skeptical listeners to understand before judging it?”

Stephinity argues that the modern scientific lens is too narrow. Not wrong—but incomplete. She sees value in:

- case studies

- pattern recognition

- field effects

- resonance models

- historical cycles

- experiential knowledge

Whether or not you agree, her challenge to mechanistic materialism echoes thinkers like Rupert Sheldrake, IONS researchers, and even physicists questioning entropic cosmology.

And she’s not claiming this replaces science. She’s asking what science misses when it refuses to look beyond the physical.

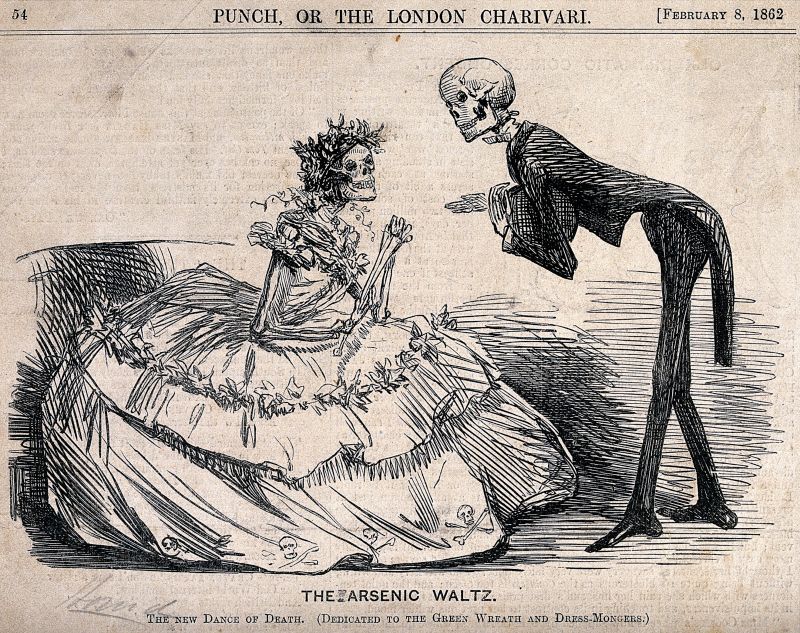

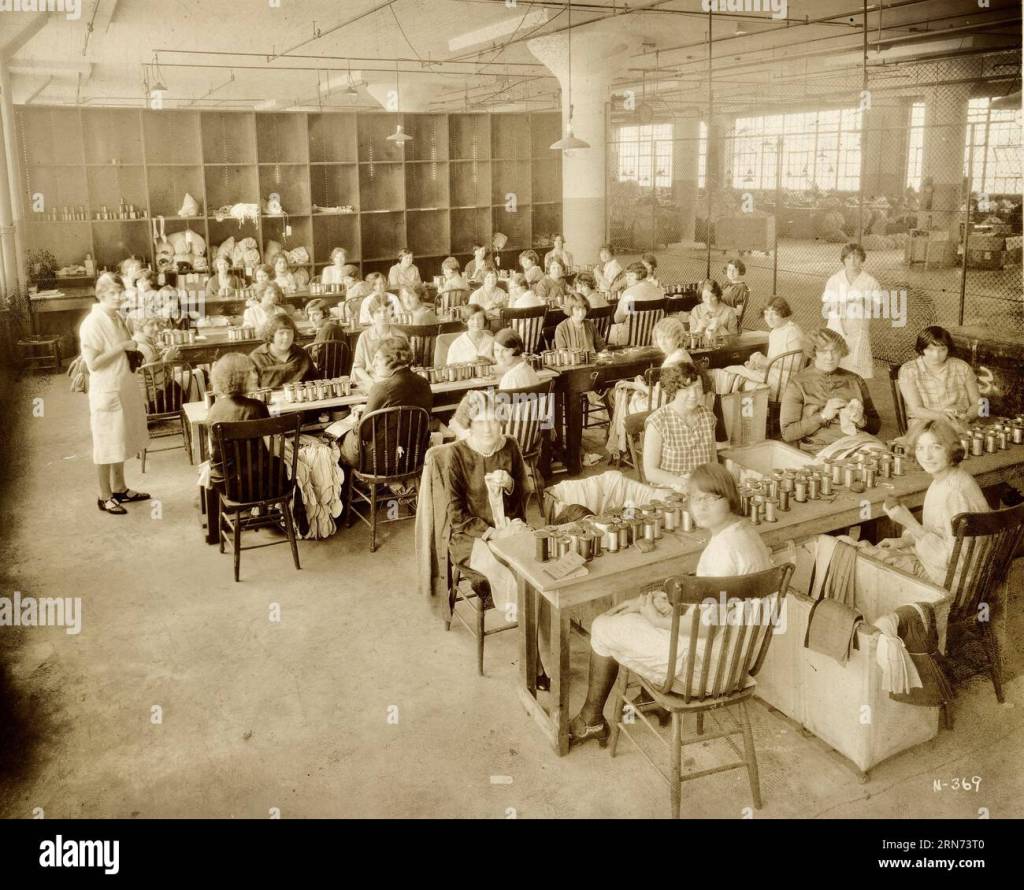

Suppression: What It Looks Like in Real Life

Stephinity’s paper covers how suppression shows up on multiple levels. Here are a few examples she explores:

- Overuse of symptom-suppressive medications

- Emotional avoidance that pushes trauma deeper

- Social pressure to conform

- Institutional censorship

- Environmental toxins that overwhelm the microbiome

- Radiation and electromagnetic exposures

She frames suppression as a terrain problem: when the body or society becomes too acidic, stressed, toxic, or disconnected, the miasm takes root.

This is where we start to cross into the biological, psychological, and social layers—which brings us to one of my favorite parts of her theory.

Neuroparasitology: When Parasites Change Behavior

This is the section I teased in the podcast because it’s both wild and backed by real research.

Stephinity references studies showing that parasites can alter host behavior not just in insects or rodents, but potentially in humans too. Her paper cites examples like helminths, nematodes, mycotoxins, and other microorganisms (McAuliffe, 2016; Colaiacovo, 2021). These organisms are everywhere, not just in “developing countries” (Yu, 2010).

Researchers have documented parasites that:

- influence mood

- shift risk-taking

- modify sexual attraction

- impair impulse control

- change social patterns

This is what Dawkins called the extended phenotype (1982): the parasite’s genes expressing themselves through the host’s behavior. Neuroparasitologists Hughes & Libersat (2019) and Johnson (2020) have shown how certain infections can shift personality traits in specific, predictable ways.

Stephinity ties this into terrain: parasites tend to thrive in acidic, low-oxygen, stressed, radiative environments (Clark, 1995; Tennant, 2013; Cerecedes, 2015). In her view, chronic suppression creates exactly that kind of internal ecosystem.

But there’s another layer here. One that isn’t biological at all.

This is where philosopher Daniel Dennett enters the chat.

In Breaking the Spell, Dennett describes “parasites of the mind”: ideas that spread not because they’re true, but because they’re incredibly good at hijacking human psychology. These mental parasites latch onto our cognitive wiring the same way biological one’s latch onto the nervous system. They survive by exploiting:

- fear

- moral impulses

- tribal loyalty

- the desire for certainty

- social pressure

- existential insecurity

According to Dennett, religious dogmas, conspiracy theories, and ideological extremes act like memetic parasites: they replicate by using us, encouraging us to host them and then pass them on.

In other words: not all parasites live in the gut. Some live in the mind.

And…..we even discussed how billionaire Les Wexner once publicly described having a “dybbuk spirit” a kind of parasitic entity in Jewish folklore known for influencing personality. Whether symbolic or literal, the analogy fits. 🫨😮

Her point is simple:

When the terrain is weak, something else will fill the space.

Whether that “something” is trauma, ideology, toxicity, or a literal parasite… the mechanism rhymes.

Collective Delusion and Mass Psychosis

Drawing on Jung and Dostoevsky, Stephinity explores the idea that societies can enter “psychic epidemics.”

You’ve seen this. We all have…

The last decade has been a masterclass in how fear, propaganda, and emotional suppression create predictable patterns:

- polarization

- tribal thinking

- moral panics

- ideological possession

- scapegoating

- censorship

- intolerance of nuance

She argues these are symptoms of a cultural miasm—not failures of individual character.

Whether you lean left, right, or somewhere out in the wilderness, you’ve likely felt this rising tension. And it’s hard not to see how unresolved collective trauma feeds it.

COVID as a Catalyst: What the Pandemic Revealed

Another part of her paper dives into how the pandemic brought hidden patterns to the surface.

Some of her claims are controversial, especially around EMFs and environmental co-factors. In the episode, we unpack these with curiosity, not blind acceptance.

Her larger point is that COVID exposed:

- institutional fragility

- scientific gatekeeping

- public distrust

- trauma-based responses

- authoritarian overreach

- the psychological toll of suppression

Whether you agree with the specific mechanisms or not, the last decade made one thing undeniable: something in our social terrain is deeply dysregulated.

8. Healing Forward: What Do We Do With All This?

If suppression drives miasms, then healing means unsuppressing. Gently, not chaotically.

Stephinity suggests practices like:

- emotional honesty

- reconnecting with nature

- releasing stored trauma

- nutritional and detoxification support

- reducing exposure to chronic stressors

- restoring community and meaning

- opening space for spiritual or intuitive insight

She’s not prescribing a protocol. She’s offering a map.

The destination is what the Greeks called sophrosyne: a state of balance between wisdom and sanity. Not blissful ignorance, not paranoid awakening. Just grounded clarity.

And I think we could all use a bit more of that.

Key Evidence and Arguments

- Stephinity critiques materialist science, calling out what she terms “entropic cosmology.” She argues that by assuming nature is strictly mechanistic, mainstream science misses field-based phenomena, non-local consciousness, and deeper systemic patterns.

- She draws on historical and homeopathic sources (Hahnemann, Kent) to build her theoretical foundation but also argues for newer forms of evidence: resonance, case studies, and pattern detection in social systems.

- On the environmental front, she explores links between toxins, EMF / 5G, biotech, and chronic disease, not just as correlation, but as evidence of suppression dynamics.

- Psychologically, she invokes mass delusion or collective repression (drawing from Jung, Dostoevsky) seeing societal crises as expressions of buried collective shadow.

- Ultimately, her call to action isn’t just for individual healing, but for systemic awakening: more transparency, alternative medical paradigms, and restored connection with nature.

Why This Matters for You

Even if homeopathy isn’t your jam, Social Miasm Theory offers a metaphor (and potentially a map) for understanding how inner repression becomes external crisis. If this episode does anything, I hope it gives you permission to look a little closer and question the stuff we’re told not to touch.

📚 Want to Dig Deeper?

Stephinity’s website: YOUR BODY ELECTRIC YOUR BODY ELECTRIC | FULL SPECTRUM FREQUENCY MEDICINE Find her on Linkden , Instagram and Substack

https://www.unifiedfield.info/

https://corbettreport.com/how-the-government-manufactured-covid-consent

Use of fear to control behavior in Covid crisis was ‘totalitarian’, admit scientists